By Mike Whaley

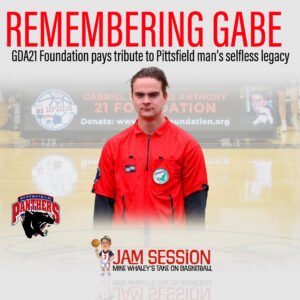

Although Gabe Anthony died much too soon at age 24, his extraordinary humanity is fittingly living on through the Gabriel Douglas Anthony 21 Foundation.

Although Gabe Anthony died much too soon at age 24, his extraordinary humanity is fittingly living on through the Gabriel Douglas Anthony 21 Foundation.

Started by Gabe’s dad, Rick Anthony, the Foundation’s mission is to supply safety equipment to all New Hampshire high school aged drivers. A year ago this past Sunday (December 15, 2023), Gabe’s automobile broke down along Route 93 South in Sanbornton and he was hit by a car driven by a woman who was later charged with driving under the influence. He died at the scene.

Gabe’s death cut a painful swath through the small town of Pittsfield where he grew up playing soccer and basketball. His dad recalls those early months trying to navigate grief and finally finding some solace by chance. Rick is a 1982 Pittsfield High School graduate and has been a physical education teacher in his hometown since 1995. He has an advisory class of 11 students that meets every school day for a 25-minute block, which gives Rick a chance to check in on them. “I’ve had the same group since seventh grade,” Rick said. “It was last March and we were talking. They were all new drivers and they were talking about how their cars had broken down.” One kid’s car caught on fire. Another had a fan belt break.

Rick remembers asking if any of them had roadside flares. They had no idea what he was talking about. “You understand why I’m saying this?” he asked. They certainly did. They just didn’t know what the flares were.

That spurred Rick into action. That afternoon he went online and found packs of three flare LED lights for $20. He bought a set for each of his advisory students. “As I was doing that, the idea for the Foundation came about. We should be doing this for everybody. Every kid this age is driving a very used car; very few have reliable cars. It’s not a matter if they break down, it’s when they break down.”

Rick started putting GDA21 together with the help of his wife, Erica, and his daughter, Sage. “They loved the idea. I just went with it.”

By June Rick had the website (gda21foundation.org) up and running – 21 was Gabe’s high school soccer and basketball uniform number. As soon as it went live, people put it on Facebook and it exploded. Over the first two weeks they raised $20,000. Since then they’ve been able to keep it going through various fundraisers, including New Hampshire Muscle Cars and the Pittsfield Balloon Rally. “We’re keeping it out there bit by bit,” Rick said. “It’s struck a chord with people.” The foundation has currently raised around $60,000.

“The idea is to go to as many schools as we can to give these lights to seniors,” Rick said. “We would do a presentation (of the lights), tell Gabe’s story and talk about how to be safe.” To add meaning and credibility to what the Foundation is doing, Rick is trying to involve local police and fire departments.

The presentation for each student includes a three-pack of LED roadside flares that can be placed behind a disabled auto. They flash as warning lights in addition to the car’s hazards.

The Tri-City Driving School in Rochester reached out to Rick. He did his first presentation there in October. “We’ll continue to fundraise and we’ll continue to get out there,” he said. Rick figures the Foundation has enough funds to do eight or nine schools. They ordered 1,000 lights through a Texas company that gave them a pretty good discount. The plan going forward is to visit eight schools in January and February: Pittsfield, Prospect Mountain, Coe-Brown, Belmont, Sunapee, Plymouth, Colebrook and Groveton.

The goal is to hit every school in New Hampshire over time. Rick said that 100 percent of the monies raised go to the lights. “We don’t use it for anything else; not for my travel. The money goes right to the lights,” he said.

Rick said his advisory group put together a video for the website displaying how the lights work. Using a dark road in Pittsfield, the video shows a car coming around a corner onto a disabled car in three situations: without its flashers on, with its flashers on, and then with its flashers on and the flashing LED lights. “The difference was amazing,” Rick said. “One of our mottos for the foundation is ‘To be seen can save your life.’”

In recounting what happened to Gabe, Rick said “He was trying to fix his car. The hood was up, the flashers on and he did everything right. That’s not me just saying it. That’s the police report saying that he did everything right. The car just plowed into him because she never saw him.”

It was an emotional end of the week for the Anthonys who were in court on Thursday (Dec. 5) for the first time for the vehicular manslaughter case against the woman who drove into Gabe with her car. The next day (Dec. 6), Rick went to Farmington for doubleheader basketball games against Pittsfield. In between the two games, Rick spoke about the Foundation and had the Pittsfield teams present roadside flares to all varsity members of the Farmington squads. Farmington folks also donated an unspecified amount to the Foundation, including the entire proceeds from the 50/50 raffle.

Rick was a little surprised how special a moment it turned out to be. When he played basketball at Pittsfield in the early 1980s, Farmington was their biggest and sometimes bitterest rival. “That’s the last thing you would think that I would be speaking over at Farmington in their gym,” he said. “That was awesome. Farmington was great. I’m very appreciative of the people over there. That was fun.”

It’s the kind of event that likely would have resonated with Gabe. “He had a passion for sports. He was passionate about soccer,” Rick said. “He liked basketball, but soccer was definitely his favorite.”

Rick said Gabe was born into soccer. When he was young, Rick was the varsity soccer coach at Pittsfield HS, a position he held for 15 years. “He kind of grew up with my soccer players,” Rick said, “being in the house for the team dinners. He liked the freedom of that a little bit more, just being outside.”

Gabe came of age playing youth sports in Pittsfield on different travel teams coached by Rick and Jay Darrah, the Pittsfield athletic director and boys basketball coach. One of Gabe’s teammates was Darrah’s son, Cam, who is a year younger. “They played together and were friends forever,” Rick said.

When Gabe got to high school, he played both soccer and basketball. “He wasn’t a scorer,” Rick said of his son in basketball. “He didn’t have to be. You had Cam and some other kids on the team who could do that. His job was to play defense and rebound. Set picks. And he did that very well. He was a really good role player. He was the kind of kid who didn’t get the accolades. He did the little things that coaches and other people notice that know the game.”

Gabe played four years on the varsity basketball team for Jay Darrah. “He was selfless with a great work ethic,” the coach said. “He did what was best for the team. He embodied that philosophy on the court or the field. He would dive for loose balls or win a 50-50 ball on the soccer field. It was the little things that don’t show up in the scorebook that he was great at. He was an exceptional teammate. He just loved being on a team.”

Darrah added: “He was very loyal. Anyone who had the pleasure of meeting him, instantly recognized his authenticity and genuine nature. He was just a likeable kid.”

Last winter, Pittsfield honored Gabe’s memory by framing his number 21 basketball jersey and placing it on the gymnasium wall behind the Pittsfield team bench. “I think that’s significant, just so we know he will always be there,” Darrah said. “The team will always be able to live off his legacy – the selflessness he provided as a player, as a person and as a soccer official.”

Gabe became a soccer official when he was 12. That evolved into a part-time vocation at which he excelled and took very seriously. “He became well-liked because he had that field awareness as a player, but also had that easy personality where coaches could talk to him,” Darrah said.

Rick recalls Gabe getting into soccer officiating. His son drew him into it. “He had to take the course,” Rick recalled. “I figured if I was driving him to games, I might as well get paid for the game too. So I did the course with him and we started doing games together.”

Gabe went to college at the University of Oregon, because his goal was to go to a big school with big-time sports. When he was accepted, Gabe flew out with his dad to visit the campus. As Rick recalled, 15 minutes into their visit, Gabe turned to him and said: “This is where I’m going.” Rick responded, “‘I’m going with you.’ It was a beautiful campus; just an amazing area.” While attending Oregon, Gabe joined the soccer board and officiated games. When he returned to New Hampshire in 2022, he jumped on the board here and by age 24 he had already done two high school state finals.

Gabe left Oregon a few credits shy of graduating. Student loans were piling up so he decided to return home to find a job and finish school online. He worked full-time with a mortgage company, while taking online classes and refereeing soccer. He had a winter passion for snowboarding, which led to him working part time on weekends at Waterville Valley Resort so he could have a pass to use the mountain when he had some free time. In fact, he was returning from a day of snowboarding with friends at Waterville Valley when he was hit.

“He was adventurous,” his dad said. “He was very likeable and very loyal to people who were loyal to him. He was brave in the fact that he loved to try new things. Even as a little guy he would walk into a tryout for youth soccer or AAU basketball. He wouldn’t hesitate to jump right in and be with people. He was good with that. He was good at meeting new people. He was friendly. He was a good kid.”

Although the pain of Gabe’s death is still very much present with the Anthonys, this way of honoring him just feels appropriate. “The idea for the family is that if one family doesn’t have to go through what we’re going through and have been through, his death is not in vain,” Rick said. “That’s the idea. If these lights save one person, it’s done its job in Gabe’s memory.”

(For more information on the Foundation go to https://gda21foundation.org)

Mike Whaley can be reached at whaleym25@gmail.com

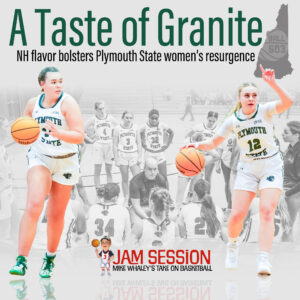

FARMINGTON – Dawn Weeks was in a bit of a pickle. It was the eve of the 2023-24 NHIAA Division IV girls basketball season and her Farmington High School junior varsity and assistant coach had just stepped down. The chances were extremely slim at that point that she could find a quality replacement before the preseason began.

FARMINGTON – Dawn Weeks was in a bit of a pickle. It was the eve of the 2023-24 NHIAA Division IV girls basketball season and her Farmington High School junior varsity and assistant coach had just stepped down. The chances were extremely slim at that point that she could find a quality replacement before the preseason began.

Haskell is a 1995 Farmington HS grad. She later played three sports at Daniel Webster College in Nashua, scoring over 1,000 points in basketball. She’s been coaching three sports at the 500 including a Grade 3-4 travel team. Her daughter, Rory, is in the program. When Weeks asked her to help out with the high school team, she was happy to do so. “I’ve been able to coach some of them at the junior high level for volleyball,” she said. “It’s such a great group of girls.”

Haskell is a 1995 Farmington HS grad. She later played three sports at Daniel Webster College in Nashua, scoring over 1,000 points in basketball. She’s been coaching three sports at the 500 including a Grade 3-4 travel team. Her daughter, Rory, is in the program. When Weeks asked her to help out with the high school team, she was happy to do so. “I’ve been able to coach some of them at the junior high level for volleyball,” she said. “It’s such a great group of girls.” Because her assistants have busy schedules that prevent them from making every game and practice, Weeks seldom has a full complement of coaches. But, she said, she consistently has at least three. She is coaching both teams – a total of 16 girls. The JVs and varsity practice together.

Because her assistants have busy schedules that prevent them from making every game and practice, Weeks seldom has a full complement of coaches. But, she said, she consistently has at least three. She is coaching both teams – a total of 16 girls. The JVs and varsity practice together. Weeks laughs. “I have tunnel vision. I’m not going to lie,” she said. “I watch the ball. It’s really great to get the breakdown of other things from people who know what they’re talking about.”

Weeks laughs. “I have tunnel vision. I’m not going to lie,” she said. “I watch the ball. It’s really great to get the breakdown of other things from people who know what they’re talking about.”

Debbie recalls the structure she had growing up with a dad who was a U.S. Marine and a mom who was a coach and school administrator. “I try to influence the girls on and off the court the same way,” she said. “I think just giving that structure to the girls is super important.”

Debbie recalls the structure she had growing up with a dad who was a U.S. Marine and a mom who was a coach and school administrator. “I try to influence the girls on and off the court the same way,” she said. “I think just giving that structure to the girls is super important.”