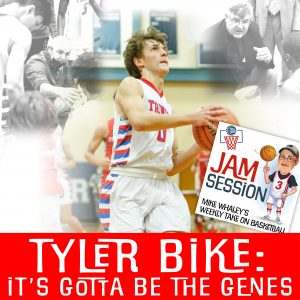

By: Mike Whaley

If you’ve seen Tyler Bike play basketball and you’re unaware of his family’s impressive gene pool, you’d still agree he’s pretty darn good. But if you knew about the gene pool, you might just say to yourself, “Well, that certainly explains that.” Which, of course, it does, except genes alone don’t get the job done. Tyler Bike knows that.

If you’ve seen Tyler Bike play basketball and you’re unaware of his family’s impressive gene pool, you’d still agree he’s pretty darn good. But if you knew about the gene pool, you might just say to yourself, “Well, that certainly explains that.” Which, of course, it does, except genes alone don’t get the job done. Tyler Bike knows that.

Bike is a 5-foot-11 junior guard for the Trinity High School boys team, coached by his dad, Keith Bike. Keith played his college ball at NCAA Division I University of Hartford, where he was a solid four-year player. Keith’s dad is Dave Bike, who was the head men’s hoop coach at Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, Connecticut, for 35 years. His teams won 528 games including the NCAA Division II national title in 1986. Before he became a coach, Dave spent eight summers playing baseball in the Detroit Tigers’ minor league system.

On the other side of the family, Tyler’s mom, Stephanie Schubert, was a basketball star at Manchester Central HS. She later walked on at the University of New Hampshire, eventually becoming a scholarship player and a team captain.

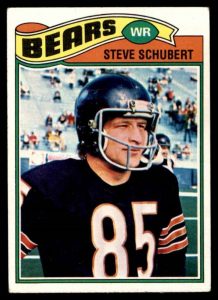

Stephanie’s dad, Steve Schubert, was also a star athlete at Manchester Central HS. He played football at the University of Massachusetts, earning All-American honors as a wide receiver. After that, he spent six years in the National Football League with the New England Patriots (1974) and the Chicago Bears (1975 to 1979). Steve is listed by Sports Illustrated as one of New Hampshire’s greatest sports figures of the 20th century.

“That’s why they pay for racehorses – the blood on both sides,” Dave Bike said. “There’s good athletic blood on both sides.”

Some pretty good athletic knowledge, too.

“After games, after anything you get different opinions on how you played,” Tyler said. “There’s diversity in it. My grandfather on my dad’s side has that basketball background. He’ll probably give me more on the basketball aspect of the game. My mom, my dad, my other grandfather, they all know as well. Having all those different opinions help me. I get to kind of choose which ones will help me more than the other ones.”

Led by Tyler, Trinity is pretty good, too, but it can get better. At 2-2 in Division I, however, they are not the same team that earned the top seed in last year’s D-I tournament. Those Pioneers lost just one game, running the postseason table to win the 2021 crown with a dramatic 64-62 victory over No. 3 Goffstown.

Gone from that team are four key players, including graduated senior Andrew Politi. Two other players transferred – Mark Nyomah (Manchester Central) and Max Shosa (Manchester West). A fourth potential starter decided not to play.

That leaves Tyler to lead the team with classmate DeVohn Ellis. Three sophomores and three freshmen play key roles behind the two juniors.

There have been some early struggles, but the year ended on a good note when Trinity won the Queen City Invitational Basketball Tournament with three straight wins. In the final, the Pioneers beat a very good Bedford team, 64-60, behind 25 points from Tyler who was named Tournament MVP.

That balloon of euphoria popped on Tuesday with a 63-60 loss to Manchester Memorial as the Pioneers renewed their D-I schedule in the new year.

Last year, Tyler was the point guard, a first-team D-I All-State pick as a sophomore. He was able to orchestrate the championship run by getting the ball to the many scoring options, most notably Politi, Nyomah and Ellis. This year, his dad wants him to score more. Although his performance at the Queen City tournament is a good sign that he may be stepping into that role, it was a challenge in the early going in D-I.

“I’ve been shooting terribly,” he said on the eve of the Queen City tourney. “I just need to go into every game with the pass-first mindset. I think as the game goes on it will start to come to me. I’ve been trying to force it recently out of the gate to get my shot going.”

His dad agrees. “He’s pressing a little bit too much to score because we need him to.”

Fortunately, Tyler is a teenage athlete who is striving to get better. He recognizes his shortcomings and embraces advice.

“That’s the best thing about him,” said Keith, who is in his fourth year coaching at Trinity and his 14th coaching at the high school or college level. “He’s not walking around thinking he’s the greatest thing since sliced bread. He’s always willing to improve and get better.”

For Dave Bike, watching his grandson play for his son is more nerve-wracking than when he played or coached. “It’s tough,” he said. “Fortunately they’re doing a heck of a job, both playing and coaching.”

Dave said when he was growing up, his dad was tough on him. “We talked about the game. But I listened. I wanted to improve.”

Keith and Tyler both embrace Dave’s advice. “That’s the thing I appreciate,” Dave said. “As tough as it is for them to listen to me after a game, I try to be as positive as possible. When I talk to Tyler I think that’s what’s going to make him a really good player and get better. He’s willing to listen. He wants to improve. Keith, too.”

Dave can recall playing a great game in high school and his dad zeroing in on an opposing player taking the ball from Dave. “My father was right,” he said. “What did that have to do with playing well?’

Dave thinks Keith and Tyler are from the same mold. “They’re willing to accept the criticism, rather than fight it,” he said. “Rather than make excuses. I hope they know I appreciate all the good that they’re doing. Being able to say ‘wait a minute, I want to get better.’ How do I get better is not only built on the positive, but try to eliminate as many negatives.”

Keith still embraces his dad’s advice as a coach, the same way he did as a player. He recalls a high school game, similar to his dad’s story, when he played at Xaverian in Middleton, Connecticut, and he had 30 points and 10 assists versus powerful Hillhouse. His dad, however, questioned why he let an opposing player take the ball from him. “I think that made me a better player,” Keith said. “Getting that from a different angle, where a lot of parents aren’t able to do that. They don’t have that knowledge of the game.”

Not like Dave Bike. “How many fathers are national coach of the year in Division II and have over 500 wins at the college level?” Keith asked. “I think he knows what he’s talking about.

“It helps me now just coaching my own team,” he said. “I call him after every game. He watches most of the games online. He tells me things I didn’t even see myself. That’s very helpful.”

Growing up, Keith certainly soaked in being the son of a college coach, starting as a ball boy for Dave’s team. “I was the slowest kid every time I stepped on the court,” Keith said. “I had a good knowledge of the game. A lot of that had to do with me watching my dad’s teams and players growing up. Just being the kid on the bench.”

Growing up, Keith certainly soaked in being the son of a college coach, starting as a ball boy for Dave’s team. “I was the slowest kid every time I stepped on the court,” Keith said. “I had a good knowledge of the game. A lot of that had to do with me watching my dad’s teams and players growing up. Just being the kid on the bench.”

Keith said it was a different generation – no Nintendo. No video games. “I’m just sitting on the bench watching every game, every practice,” he said. “After they were finished I was able to get on the court and shoot. Actually, when I was older my dad let me participate in practices and certain drills when I was good enough.”

Oddly enough, while Keith looked forward to coaching his son, Dave did not. Keith remembers getting recruited by his dad’s assistant at Sacred Heart without Dave knowing. “My dad never wanted to coach me,” Keith recalled. “He was in that mindset.”

Dave, even now, remains unsure about coaching his son. “I still don’t know what the right thing to do is,” he said. “I backed off. He could have come here (to Sacred Heart) and played for me. I tried to talk to a number of people and I still don’t know what the right thing to do is.”

Dave knows this: “It worked out well for him and Tyler last year. I guess it worked out well for Keith being his own man.”

Although Keith never played for his dad, he did coach with him. After he graduated from Hartford, he spent seven years as an assistant coach at Sacred Heart under Dave.

As for coaching his son, Keith said, “I have a different mindset. I want to coach my kid.”

He first did it in middle school when Tyler was in seventh grade. Keith was not pleased with that outcome. “I was really hard on him,” he said. “I felt I was too hard on him. That wasn’t helping.”

Keith had run into that problem at his first head coaching job at Manchester Memorial High School from 2005 to 2008. “I was a little too tough on the kids,” he said. “I came directly from college so I was expecting them to be college ready. You learn a lot as you coach – more experiences give you the opportunity to grow.”

It comes back to sage advice from his dad. “Once you think you’ve learned it all, that’s when you’re going to be in trouble,” recalled Keith.

Still, if Keith felt being hard on Tyler had a negative impact, his son thought the opposite. “No, it was great in middle school,” said Tyler, who was the only seventh-grader on the A team. “It kind of gave me an awakening. He had to be a little harder on me than the other kids. That kind of helped me.”

Once Tyler got to high school, Keith laid it out: “I told him, listen, I’m going to play the best players. If you’re one of the best players, you’re going to play.” Keith told the same thing to Ellis and Nyomba. “If you’re ready, you’re going to play,” he said. “If you’re not, you’re not going to play. And they were ready.”

Things have run smoothly at Trinity. The father-son thing has not been a distraction. “I’ve been lucky,” Keith said. “My kid has been one of the best players in the state the last couple of years. I’ve also been lucky to have great parents and lucky that he’s a great kid and the parents like him. The players like him. There haven’t been any issues – knock on wood.”

“(Tyler) was ready to be good. He wanted to be good,” his dad said. “I didn’t have to do much. That’s something my father taught me. If you’re going to do this, you’re going to do this right. I think he’s prepared himself.”

The Schuberts like what they see in Tyler as well. “He’s a real hard worker,” said his mom. “He doesn’t take anything for granted. He works really hard to be the best that he can be. I think that’s what impresses me the most about him.”

Although Stephanie and Keith are no longer together, they have maintained an amicable relationship and remain close geographically. She lives in Merrimack and Keith in Bedford with his new family – wife, Cortney, and their four young children. Stephanie and Keith have an older daughter, Keira, who played four years of basketball at Merrimack HS, where she graduated in 2021.

When Stephanie talks to her son about basketball, leadership is one topic she stresses. “How can he be the best leader dealing with all the personalities on the court?” she said. “He’s a point guard and he’s just by nature a leader.”

Like his mom, who was a point guard at UNH.

“A lot of the conversations we’ve had over the last couple of years are how can you get the most out of your teammates,” Stephanie said. “The psychology around being a good leader. And defense – I always tried to be the defensive player. I always tell him that defense will bring offense to you.”

Steve Schubert is just having a blast following his grandson’s evolution as an athlete. “I like to watch him play, watch him grow and watch him become a man,” Steve said.

He doesn’t offer too much in the way of advice, other than to say “it’s just a matter of staying in shape, working hard, being a good person and being a good student,” Steve said. “And enjoying what he’s doing and what he’s accomplishing. I think it’s excellent.”

Steve played basketball at Central – the classic football guy on the hoop team. One of his teammates was a fellow named Stan Spirou, who went on to a successful career coaching the men’s hoop team at Southern New Hampshire University (640 wins in 33 years).

Offense was not a big part of Steve’s game. He was a rebounder and defender first and foremost. When he watches a game, his focus is on the stuff done in the trenches, like he did back in the day. “I just sit there and say they’ve got to box out,” Steve said. “Basics. Just put a body on somebody and box out. You’re not trying to hurt anybody. You’re just trying to get position. That’s all you’re trying to do. That’s important. Keith says that. I hear him. That’s a big thing.”

He also knows a thing or two about playing at the next level. A point he makes and everyone agrees on, including his grandson, is that Tyler needs to get stronger. “Be smart. Don’t screw up your shot,” Steve said. “But get stronger.” Tyler has a strength and conditioning program that he uses, which was set up by his cousin and Steve’s nephew, Charlie Schubert.

One big asset that Tyler has from his Schubert side is speed. “He got that from his other grandfather,” Dave Bike said. “None of the Bikes could run. They used to say I ran in the same spot too long.”

The next level is on Tyler’s radar. He has goals. “My dream school is Villanova,” he said. “That’s what I’m shooting for. I just need to work hard and I think I’ll be able to get there.”

When he lists what he needs to do to get to the college level, getting stronger is right there at the top – along with becoming smarter and a more consistent shooter. “Those are the three things that kind of stand out for me,” Tyler said

Keith can see his son at the next level as the 5-foot-11 point guard that he is. “I watch college basketball and see 5-11 point guards controlling the game,” Keith said. “I can see him doing that. He’s got to get better. He knows that.”

Stephanie adds: “He’s a very level-headed kid. He’s very, very smart. He respects the people who offer him all this great advice. He kind of sits on it and continues to work on his game. He doesn’t let it rattle him; the fact he has all these Schuberts and Bikes telling him some of the things he has to do better. He soaks it all in.”

Tyler laughs, admitting that there are moments when he experiences family-advice overload. “There’s definitely times when I don’t want to hear it,” he said. “I’m like, ‘all right, no one say anything. Let me go to my room.’”

Which, of course, is all part of the learning process.

Have a story idea for Jam Session – email whaleym25@gmail.com.