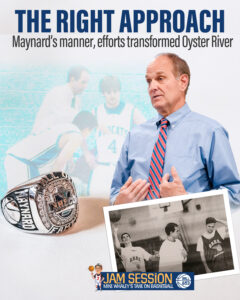

By Mike Whaley

(This is the sixth in a series on the 2025 NHIAA state championship basketball teams.)

While winning a state championship is the ultimate goal for any high school basketball team, most coaches will tell you that they’d like to approach the season one game at a time so as not to get caught looking too far ahead.

While winning a state championship is the ultimate goal for any high school basketball team, most coaches will tell you that they’d like to approach the season one game at a time so as not to get caught looking too far ahead.

Pembroke Academy boys coach Mike Donnell did not have that luxury. The team was pretty adamant since losing in the 2024 semifinals that this season it was “championship or bust.” It was a no-choice adjustment for the coach. “I don’t like coaching that way,” he said. “I like to take it the old-school way – one game at a time. Not these guys. They wanted this ’ship badly enough. We had been so close three years in a row. They wanted to do what the other teams couldn’t do and that was to finish.”

Senior Devin Riel recalls he and classmate Evan Berkeley meeting with coach Donnell before the season to discuss goals. “We told him it was ‘win or bust.’” Riel said. “We either were going to win the state championship or it was going to be a bust.”

While it was an adjustment for Donnell and his staff, they did use it to their advantage. “Every time they got a little lazy at practice, we’d whip them back into shape and say ‘you’re the guys who want a championship. You’re the guys saying ‘championship or bust.’ So let’s go.”

Well, the Spartans did just that. They went through the regular season 16-2 to earn the top seed, and then swept their three playoff games. In the final, they stopped Sanborn, 63-54, to capture the program’s ninth Division II state championship, the most in the division.

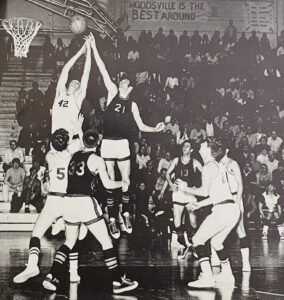

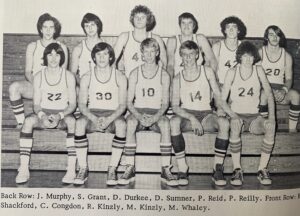

Pembroke has a rich basketball tradition going back to the 1960s when it won its first state title in old Class I, a 56-52 win over Littleton. Pete Kaligian was the coach. Hall of Fame coach Ed Cloe guided Spartan teams to four crowns in 1972, 1978, 1985 and 1991 during a 30-plus year run, and his former star, Matt Alosa, carried on the tradition with back-to-back titles in 2013 and 2014. Rich Otis led the team to the 2019 championship, and Donnell was at the helm this past year. Donnell has been part of the last four titles as either a head or assistant coach.

There was some heartbreak before Pembroke got to the pinnacle in 2025. Donnell took over as head coach half way through the 2021-22 season when Otis resigned amid pressure from a group of parents. The Spartans lost in the quarterfinals that year, followed by a loss in the 2023 championship to Pelham, and last year’s painful defeat in the semis to Hanover.

“The bar was set from the moment we lost last year,” said Riel of the 49-43 loss in the semis to Hanover. “A lot of guys wanted it a lot more. We knew we couldn’t let that happen again watching the seniors cry. It was probably the worst bus ride I’ve ever been a part of. It was sad. It was depressing. It was a feeling I never wanted to feel again. That’s why our bar was so high.”

Berkeley agreed, saying, “Our main focus was having that last bus ride home from UNH and being all excited that we won the championship.”

Now it was just a matter of getting there and getting it done. Berkeley and Riel were the senior anchors along with classmate Owen Stewart. They were joined by a solid junior class with Zac Bemis, Colin Dube and Javien Sinclair, and talented sophomore Andrew Fitzgerald. It was a small team with the key players all in the 5-9 to 6-0 range with the exception of Sinclair (6-foot-3).

Berkeley and Riel took vastly different journeys to the varsity team. Berkeley grew up playing basketball. He was on the junior varsity as a freshman, swinging up to the varsity at the end of the season. As a sophomore, he was the second man off the bench, getting 10 or so minutes per game. As a junior, his role expanded to starting point guard and the team’s second leading scorer behind senior Joe Fitzgerald, Andrew’s older brother. “I had to take control of the floor and start running the offense,” he said. “I knew the work I had put in. I knew I would be the right person for the job.”

Riel didn’t focus on basketball until he got to high school. He was a baseball-only player before that. Knowing that Pembroke is a basketball town, he decided to give that sport a shot. He played with the freshmen team his first year, swinging with the JV squad as well. As he started getting better and showing more interest, his role expanded. He was the JV captain as a sophomore. Between his sophomore and junior year was when everything took off. He had a big growth spurt, going from 5-8 to 5-11, and he took offseason training and what the coaches said more seriously. As a junior, he became one of the three main guys with Berkeley and Joe Fitzgerald. “I really started to buy into my role,” he said. “My role was a lot more on the defensive side. I would guard the best player. I would do all the dirty work. I started to love and accept that role. Whatever I had to do to win, that’s what I was going to do.”

As if it wasn’t hard enough to focus on getting better at basketball, the team also had to deal with some emotional trauma: Coach Donnell’s cancer diagnosis in the spring of 2024. “That was a season I never thought I would coach again,” said Donnell, who has coached in Massachusetts and New Hampshire since the late 1970s. Most recently, he coached under Alosa at Pembroke for three years and two championships, guiding teams at Epping and Franklin, before returning to Pembroke to work under Otis in ‘21. “I didn’t even know if I was going to live.”

Donnell said he had a colonoscopy in April of 2024. His doctor came in and said he had colon cancer. He was operated on in June of that year to remove a five centimeter tumor and 14 inches of his colon. From that point until November leading into the season, Donnell followed an intensified regimen to battle the cancer, taking 14 chemo pills a day and infusions.

“Six days after my surgery, my doctor told me to take at least a month, a month and a half off from school. To take it easy,” said Donnell, who has taught at Pembroke since 2012, currently as a transition lab teacher, helping freshmen to survive four years of high school. “When you have cancer and you have my type of personality, sitting down in a chair just makes your mind go in so many bad places and thinking of the negative side. My goal was to try to feel normal. I was back in school within six days of my surgery.”

Donnell received pushback from his athletic director, who felt he should be home resting, so that he would be good to go when the season started in November. But the school ultimately backed his decision to return. “They were all very supportive of when I needed to leave, I could just go,” he said. “The support from the school and the community was amazing.”

Perhaps the most difficult aspect of the cancer was telling his players and trying to keep their emotions in check. “It’s a tough pill to swallow,” Donnell. “I am not a closed book. I am very open. I share everything with my kids. We talk about lots of life lessons. I think that’s very valuable in coaching. We had a get-together and I told them what the situation was. I wouldn’t be around much during the summer if I was sick. If I was well enough, I would be there.”

Donnell recalls one day being approached by Riel in the weight room while working out. “I was just sitting there and not being very comfortable,” Donnell said. “He (Riel) came up to me and said ‘Coach, I want you to remember something. You told me and the boys if you want some done (badly) enough, you’ve got to fight for it. Coach, this is your fight. This is your championship. You’ve got to beat this and we’ve got your back.’”

That was a game-changer for Donnell. “I think from that day, my attitude about everything changed,” he said. If it wasn’t for the assistant coaches, I don’t know what would have happened. I didn’t have much energy. It takes a little over a year to get fully back from it. I’m still dealing with a few little things. My assistant coaches (Jim Cilley, Julia Labrecque and Corey Nelson) just carried the torch. They kept telling me to relax. I pretty much sat back in a chair and watched what was going on. I talked as little as I could, They pretty much ran all our summer and fall ball (programs), which was huge for us.”

The strength of the players through the whole cancer experience was amazing in Donnell’s eyes. “I know that Andrew Fitzgerald had lost his grandfather (to cancer) shortly before my episode,” Donnell said. He went up to his grandmother (a Pembroke teacher): ‘Is Coach Donnell going to die?’ So they were really concerned about me. I can’t count the amount of hugs, the words, the affection, these kids showed to me. I think it was extremely important to my healing process.”

Riel said it was a tough time for the players as well. “It hurt a lot,” he said. “We know he’s a big people person. He’s good with the community. He’s good with kids. He’s good with us. He knows how to talk with us. Like a family, he knows how to keep us close. It was a big hit for the program. We took it well though. We have strong faith in Jesus Christ. We all go to church together. We all prayed for him. He was able to get through it. He wasn’t going to fight it alone. We were going to be right there with him.”

“We knew it would be a tough battle,” Berkeley said. “Cancer is never easy. We knew Coach had the strength and the courage to do it. We were definitely riding behind him through it all. Just staying confident, praying to the man above, and loving each other and enjoying the moment.”

The Spartans started the season with four straight wins, including three over tournament teams from Manchester West, Hanover and Hollis-Brookline. Then they ran into Pelham on the road – the two-time defending state champions. Berkeley got in foul trouble and the Pythons just played better, claiming a 64-53 victory.

“I think a lot of kids put the weight on their shoulders and they had to do it (all) themselves,” Donnell said. “When you do that, you make mistakes. Instead of looking for the best shot, we were shooting the first shot. We were getting a little weak on defense, a little weak in rebounding. When you do those things (poorly) especially against a great team like Pelham, you’re not going to win.”

In the locker room after the game, the players were down. Several were crying. Donnell said he snapped. “I said, ‘Hey listen, we’re not going to have an undefeated season. You guys said you were playing to win a championship. This is one game with many more to go. Get your heads out of your butt and let’s move forward.’ From that point I think the kids bought in at practice about the ‘we over me.’ They really came together as a unit and had a very great season.”

It was a wake-up call for Fitzgerald. He played quite a bit as a freshman, giving the Spartans an offensive boost as one of the first players off the bench. But as good a scorer as he was, he was starting to realize that he needed to expand his game if he wanted to play in college, especially on defense where at times he was a liability. The Pelham game was the first game where it dawned on him that “I need to play defense. I was getting beat full court. I was getting beat off the dribble a lot. I wasn’t getting a lot of rebounds. It was the kind of realization.”

The coaches kept on him to focus on his defense. He started taking it personally. “It really motivated me to play better,” Fitzgerald said. “It looked bad on my part and it made us look bad. It was actually a little embarrassing because I was (often) a detriment (on defense).”

Pembroke did not lose again until late in the season to Coe-Brown, a 67-61 setback to end a nine-game winning streak. “The tough part is they came into our house and gave us our first (home) loss in over two years,” said Donnell. “I think after that loss in the locker room the boys were pretty adamant that they would not lose again.”

Riel recalls that loss. “We kind of overlooked them and came out sloppy,” he said. “They played a really good game. They hit their shots. We were kind of falling apart on defense. Coach Cilley, our defensive coach, got on us the next day. We watched film. He made us work. We got better at our zone. We got better at our man.”

Riel felt that loss helped the Spartans to regain focus. “I think that one fueled us a little bit more,” he said. “That one stung a little more. We got a little more fuel and that one motivated us.”

Pembroke won its final two regular season games over Merrimack Valley and Milford to improve to 16-2 and earn the top seed for the D-II tournament. With it came a first-round bye. Donnell did not like that. “Having a week off for a high school team is not good,” he said. “You practice five days that week without a game. Things get a little long.”

Not everyone felt that way. “The bye could definitely hurt some teams,” Riel said. “But it didn’t hurt us. It was a chance to rest and get our bodies back to 100 percent and ready for our first playoff game.”

The quarterfinal game was against No. 8 Bow, a team they had played and beaten on three previous occasions during the regular season and in the holiday tournament. Two of the wins were close, including the last game at Bow in overtime. The law of averages was against them, but Pembroke was not going to let that get in the way. “Our boys would not be denied,” Donnell said. “We won all four games. That was very rewarding.” The playoff win before a full house at home was by a score of 74-60. Riel and Berkeley led the way with 22 and 21 points, respectively.

For the third year, the Spartans were back in the semis. Their opponent? Pelham – their recent nemesis that had beaten them earlier in the season as well as in the 2023 championship game. “As soon as we hit the tournament, our attitude was very simple,” Donnell said. “It was ‘win or go home.’ That’s how it was. It was real.”

Donnell has always been able to read his players, so he can get a feel for them during warmups. “Just watching their actions and reactions, their shooting, what kind of energy they have,” he said. “We went into that playoff game (against Pelham) with an extreme amount of energy. I just felt really good about that game.”

His “feeling” was justified. The Spartans vaunted transition game kicked in to open up a 29-20 lead at the half. After the Pythons closed the lead to two after three stops (36-34), Pembroke regrouped in the fourth quarter to pull away for the 57-42 victory. Fitzgerald led the way with 18 points. Berkeley added 13 and Bemis and Riel split 16. “That loss (during the regular season), everything happens for a reason,” Riel said. “I think that loss is the reason we were able to win in the final four.”

Now it was on to the final at UNH. In the way was Sanborn, making its first-ever championship appearance against a program that had won the most D-II titles (eight).

The key to this game in Donnell’s mind was to shut down one of Sanborn’s two big scorers – Chase Frizzell and Dylan Rego. “I thought if we could shut one player down, our chances would be extremely good to win the championship,” the coach said.

It proved to be a sound strategy. Sinclair defended Rego, holding him to four points, all in the first half. “Whenever the ball was below the free-throw line, we just had Javien get in contact with Rego and he completely shut him down.”

Frizzell did score a team-high 22 points, but Donnell felt he had to shoot more and do more to make up for Rego, and that was an advantage for the Spartans.

The second key was that Fitzgerald went off for a career-high 26 points, 19 of those in the first half. He scored 44 points in the semis and championship combined. “I was just able to play in the flow of the game,” he said. “I let the game come to me. The shots were just coming.” Fitzgerald remembered his dismal performance in the 2024 semis against Hanover, his final game of that season. “I actually kind of folded under the pressure,” he said. “I think that was a really good lesson for me at the time. I just had to trust the work that I put in.” Trusting his work led to big scoring nights in the two most important games of the season on the biggest stage in the state.

It was tied after the first quarter and Pembroke had a two-point lead at the half. “The game got close a couple of times, but I think honestly we were in control the entire game,” Donnell said. Berkeley was a factor late in the game making foul shots (he was 9 of 12 from the line and scored 15 points). The Spartans finally pulled away to win 63-54.

The beauty of Pembroke’s approach to offense was that they didn’t care who did the scoring. When Fitzgerald heated up later in the tournament, Riel said it was simply a matter of embracing the words of Coach Donnell: “Coach talked about it. Whoever’s hot, get them the ball. We kept feeding him (Fitzgerald) the ball and he kept showing up every possession.”

The Spartans’ final record was 22-2, which included three wins to capture the Capital City Holiday Tournament title. The postseason honors also rolled in. Berkeley was named D-II Player of the Year and made First Team All-State. He has been recruited to play at Plymouth State next year. Riel was selected to the D-II Second Team and Fitzgerald was honorable mention. Labrecque was named Subvarsity Coach of the Year.

After losing in the 2024 semis, Pembroke was on a mission. As a unit, they joined a local gym to work out together. “That became the new hang-out spot,” said Berkeley. “We played at the gym with the guys and (were) going hard and going at each other. But also loving each other at the same time. You can’t be fighting with the guy you’re trying to win with. We knew we just had to buy in together and love each other and be confident in each other and that would end up working out.” Lo and behold, it did.

Whaley can be reached at whaleym25@gmail.com