By Mike Whaley

(This is the fifth in a series on the 2022 and 2024 inductees into the New Hampshire Basketball Coaches Organization’s Hall of Fame. The stories will run periodically during the winter season.)

It’s funny how things work out. In 1976 George H. “Buddy” Trask III and his future wife, Mary, were all set to throw caution to the wind. They were heading to Florida without a definite plan other than to try to find work as teachers and coaches.

It’s funny how things work out. In 1976 George H. “Buddy” Trask III and his future wife, Mary, were all set to throw caution to the wind. They were heading to Florida without a definite plan other than to try to find work as teachers and coaches.

It was Labor Day Weekend. Buddy was finishing out his job for the Mount Washington Cog Railway. The seasonal position ended in October and then Buddy and Mary were headed to the Sunshine State.

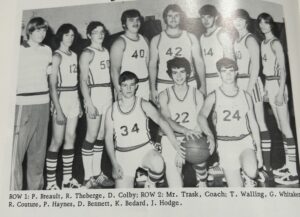

Both young Plymouth State University graduates tried to find teaching jobs but with no luck. The telephone situation at the Cog Railway wasn’t perfect. You didn’t get calls. You got messages. Sunday morning of that weekend, Buddy had a message from Mary Nugent, a teacher at Stratford High School in North Stratford, where Buddy went to school. He called her and was told that Stratford’s physical education teacher had left for another job. Could Buddy come in and substitute? Of course he could.

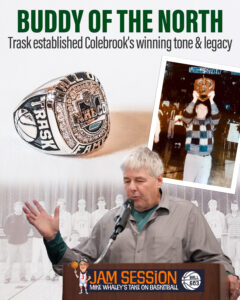

That phone call opened a door to teaching and coaching that spanned 45 years in the North Country. Buddy went on to teach physical education and coach soccer and basketball at Stratford and then Colebrook Academy. At the Academy, he was the force behind pushing the school’s athletic teams into the spotlight. When he got there in 1980, Colebrook had never won a state championship – in any sport. When he retired for good in 2022, the state titles count was 12 under his watch (the girls hoop team added the school’s 13th in 2023). Three of those championships were for boys basketball coached by Buddy, including the school’s initial state title in any sport in 1997. He is one of five high school coaches in New Hampshire with 600 or more wins in basketball with 606, all for boys. The others? Dan Parr (704, 627 boys, 77 girls), Dave Smith (669 boys), Gary Jenness (641 girls), and John Fagula (624 girls).

The Colebrook gymnasium was renamed Trask Gymnasium in 2022 after Buddy and Mary, who have a combined 70-plus years of coaching and teaching between them.

In addition, Buddy was the perfect ambassador for the North Country, representing the northern schools on various New Hampshire Interscholastic Athletic Association (NHIAA) committees for more than a quarter of a century. “The North Country got well represented,” said Jenness, who coached at Groveton and White Mountains.

Last November, Buddy was one of seven inductees into the New Hampshire Basketball Coaches Organization’s Hall of Fame in Concord. The NHBCO honored its 2022 and 2024 classes.

Back in 1976, of course, Buddy didn’t envision the longevity or the success. He was just trying to get going in life. The railway was accommodating when Buddy told them of his work opportunity at Stratford HS. “I was supposed to stay through the fall,” he said. “‘I might be back in a week. I’ve got to take this. They said ‘go ahead.’”

Monday he packed his stuff to head to Stratford where his mother still lived, so he had a place to stay. Tuesday he was sitting in a teacher’s meeting and Wednesday he was teaching. It was a good fit for Buddy. He had gone to school there, so he knew all the teachers. “I knew the system. I knew how the classes went,” he said. “I knew all that stuff. I wasn’t going in (blind). Except I wasn’t planning on teaching (there) two days before.”

A week later he was called into the office. They liked what he was doing. Did he want the job for the rest of the year? “I obviously said ‘Yes,’” Buddy chuckled. “Sometimes it comes down to luck. Who knows what would have happened if we ended up going to Florida? I have no idea what the deal would have been.”

His contract at the time was $5,200 for that school year. He was also asked to coach basketball and baseball. Within a month he added athletic director to his work load. Ken Grimes, one of his old baseball coaches, approached him with a folder. “‘I know you want to be the athletic director,’” Grimes said. “‘Here’s the folder. I’ll go up to the office and tell the principal that you’re the new AD.”

Grimes and Larry Clough were the baseball co-coaches when Buddy was in high school. When he was a junior and a senior they let him and several other players do some coaching – making the lineup, coaching third base. “They wouldn’t let me go hog wild,” Buddy said. “But they kind of let me do stuff, which was very nice of them at the time. I guess they saw something in me that I didn’t see.”

You’re thinking that Buddy coached basketball for 45 years and won 606 games, so right out of the gate his teams were successful. Right? Wrong. “It was an experience. My first year we were 2-18,” he recalled. “Stratford was definitely in a downturn at the time.”

Buddy did not make it easy for the Stratford kids. “It was the Bobby Knight era,” he said. “There was a lot of running, a lot of discipline involved. A lot of ‘who’s the boss!’ This is how I’m going to do things. … Those kids hung tough. They stuck with it. I give them all the credit in the world. I was probably not the best person to get along with.”

Stratford certainly wasn’t winning games. Buddy’s close friend Dale Ramsay recalls he was home from Keene State College for an extended six-week winter break because of the energy crisis. The first thing words out of Buddy’s mouth when he saw Ramsay was hardly a greeting. It was a no-nonsense announcement: “‘You’re coaching the JV team.’ He didn’t ask me. He told me.” It was a whirlwind schedule. Buddy had scheduled 12 games in six weeks. “We went 1-11. It was a miracle we won one,” Ramsay said.

The one game on the schedule that presented itself as a possible win was Orford, which is no longer a school (it’s now part of an interstate school Rivendell Academy. It plays in Vermont with the Green Mountain State towns of Fairlee, West Fairlee and Vershire).

Ramsay and Buddy remembered the game. “We’ve got a chance,” Ramsay said. “We’re in the game. Buddy gets a technical to fire everyone up. We end up winning.”

Buddy remembers getting back to his house at midnight and he and Ramsay celebrated. “We stayed up until six in the morning because I didn’t know if I was going to win another game,” he recalled. “Fortunately, Orford came to our place.”

That was the inauspicious beginning. It got better. From two wins, his teams won 8, 10 and 11 games at Stratford. Jenness recalls reffing some of those Stratford games, which were hard to officiate. “They had some talent. They were quick,” he said. “I don’t know if he called it a scramble defense. I called it kamikaze because they were all over the place. Everywhere he coached he just made them better than they really were.”

Buddy had some good groups coming up at Stratford. He was getting excited and then in 1980 he got called into the office again. This time the news was not so good. His teaching job was being cut in half. That wasn’t going to work for Buddy, even if he was living at home.

As Buddy recalled, there were some Stratford teachers who lived in Colebrook and they really liked him. He wanted to see through the current Stratford group, but the pay was a problem. A job opened at Colebrook. He went in for an interview with the School Board, superintendent, principal and an elementary school teacher. “I go in for the interview. Every single question was about athletics,” he said. They weren’t having me there to teach. The teaching was a secondary job. Athletics was the job.”

Buddy pauses for a few seconds. “I got the job,” he said. “There I was for the next 40-something years.”

The job description was full. Not only did Buddy teach elementary PE, but he was also the athletic director and coached three high school sports: soccer, basketball and baseball. That didn’t last long. “We were Class M when I got there,” he said. “Sixty to 70 percent (of the athletes) played three sports. I kind of realized that come March, they’re probably sick of me and I’m sick of them.” He cut baseball loose after a year or two.

But he was still very busy. In fact, once he married Mary and she got a job teaching PE and coaching at Colebrook, they rarely saw each other for a 25-year span. Mary coached the girls soccer team, winning a state title in 2002 with their daughter Corey on the team. She was also an assistant coach with the girls’ hoop team.

Buddy remembers his third year was his first year going to the playoffs at Plymouth State as the Colebrook coach. They traveled down in limousines. “Well, this Colebrook thing isn’t bad,” he thought. “If we make the playoffs, we’re all going in limos. That apparently was a one-year deal.”

Those early years were a struggle for the most part. Class M was too big. Eventually they were able to get to Class S where they belonged. Another challenge Buddy had to contend with was established coaches at the younger levels who were doing their own thing. “My deal was I can always fix it when it gets to me,” he said. “After a while I knew that wasn’t happening. There had to be a revamp at some point, which would happen.”

What was concerning was that Buddy had several losing seasons in a row. What quite possibly held things in check was that he had better success at soccer, a sport where he had less experience. “The soccer was taking off so you didn’t hear much about basketball,” he said. He coached soccer for 27 years at Colebrook over two tours, winning 242 games and making 24 tournaments, including a trip to the final in 1994 (3-1 loss to Derryfield).

As the 1980s came to a close, Buddy was able to start making coaching changes at the younger levels. “By then I had been around long enough. I had some of my kids who had played for me involved in taking over the elementary program, etc. We were getting our basketball level up to par. Gradually we started to have some kids.” The good groups began to come.

Buddy always told his youth coaches that he wanted two to three new players every year to come up and help the team. If there were more, even better. “They didn’t have to be really good,” he said. “I wanted two or three people who were going to stay with the program. We run a hard program. They weren’t going to quit. They were going to be able to deal with the stuff we were throwing at them and stay. We gradually started to get that.”

Indeed Buddy was hard. He practiced six days a week, two and half to three hours a day in the preseason, and then two hours a practice once the season started. As he got older and smarter, he joked, he shortened the lengths, but the difficulty factor remained.

“Those kids had to be prepared mentally and physically,” he said. “Hey, when you come to our program and when you get done with our program, you know you’ve accomplished something. You’re going to be ready for anything in life that’s going to be thrown at you.”

The big thing with Buddy was no excuses. “That was a key word from day one. There are no excuses. I don’t want to hear anyone talking about the officials or a mistake anyone else made. We lost because we didn’t do the things we needed to do. We need to get better.” Which they did.

The first season Buddy noticed the turnaround in motion was 1989-90 when a team led by Dan Fournier made the quarterfinals. The following year they got to the finals against a strong Epping squad that was in the midst of a three-year title run in four years. The Blue Devils were a heavy favorite to win. Colebrook earned its berth by edging Orford (remember them?) in the semis by a point. “Once we got over the initial shock of being in the final, I was thinking I hope we score in the first quarter and don’t get embarrassed.”

Colebrook did not embarrass itself. Far from that, they made it a game. They were ahead of Epping at times in the first half. They ended up losing by a very respectable 62-54. They felt really good about the following year with a lot of their top players back. What Buddy did not factor in was the huge leadership void they lost when Quinn Hurlburt graduated. “You don’t realize it at the time. He was the leader on the floor.”

The following year the Mohawks had a very good season, earned a first round bye and played a less formidable Epping squad in the quarters with only two returning starters versus the four that Colebrook had. Epping blew them out by 15. “That was a huge downer,” Buddy said. “But we were on our way just the same.”

From 1993 to 2000, Colebrook was winning 80-percent of its games. Now they were getting to the semis or the finals almost every year. “We were there. Group after group was coming. Everything was clicking.”

Of course, Colebrook had its history still hanging over its head. The success was changing, but the number of championship banners remained the same – zero. Buddy knew one was coming.

That first championship group came in as freshmen in 1993-94, led by Lance Boire, Adam Martel and Travis Haynes, a strong core of three-sport athletes. They had excellent leaders that helped set the tone when they were younger.

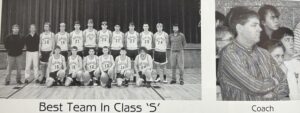

By the time they were seniors, they were ready. They lost one game during a season in which they did not have a lot of close games. Profile provided the staunchest opposition, beating the Mohawks once and losing by a handful in the second. In the playoffs Colebrook stopped a tough Stratford squad in the quarters, and then overwhelmed high-scoring Nute in the semis by 20.

Their opponent in the final was surprising Alton, but Colebrook looked like it was going to get it done, carrying a double-figure lead into the fourth quarter. Buddy mentioned a big key is trying to win at the end of the quarter, and they did it three times. The Mohawks hit a 3-pointer at the end of the first, had a steal and layup to go into halftime, and another 3 to conclude the third, Eric Biron’s only hoop of the game.

Eight minutes to go. “Fourth quarter,” Buddy said. “Colebrook has never won a championship. Ever. In anything. That’s all these kids have heard about for years.”

Colebrook started to feel that pressure. Things began to unravel. They did things they didn’t normally do. When Alton slapped a press on, usually the Mohawks would have had no trouble with it. They turned the ball over. Alton hit some shots. Down to the final minute and it’s anybody’s game.

“We were playing conservatively,” Buddy recalled. “We were playing not to lose. Usually when you play not to lose, you lose.”

Colebrook had the ball in a tie game with under a minute to play. Twice they hit one foul shot to go up two points. Defense was huge. Always a zone guy up until that point, Buddy was convinced to go man-to-man with the help of his then assistant coach Tim Purrington. Man-to-man defense became especially necessary on the big floor at Plymouth where the season concluded. “With this group we changed to man,” he said. “Teams even then were learning to pull (the ball) out. At some point we’re going to need to be able to play man. We might as well be able to play it all the time.”

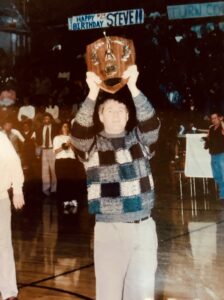

With under 10 seconds to play, Alton had the ball on the end line under Colebrook’s basket. They had to go the length of the floor to tie or win it. “We were not going to lose to them,” Buddy said. “We were playing to win. We manned up; denied up, stole the ball and we won. … When push came to shove, they defended and they won.” Final score: Colebrook 52, Alton 50.

Bedlam. Euphoria. You name it. “The town of Colebrook went nuts,” Buddy said. “The line of cars, fire engines and stuff from Twin Mountain to Colebrook was like three miles long. When we got to town, they had fire alarms going off everywhere. It was an amazing, amazing scene. The gym was full – 600/700 people. The monkey was off.”

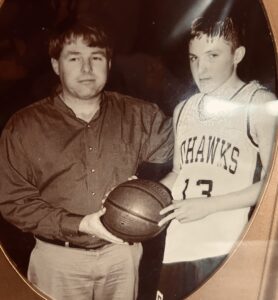

Colebrook was always in the mix for the next 15 years. Good groups kept coming. At that point, Buddy’s son, Kevin, was nearing the age when he could play for his dad. He played four years for the Mohawks, scoring a school-record 1,645 points. Buddy remembers that even as a freshman, Kevin was drawing specialty defenses to stop him. They had their moments too, but most of that was early on when Kevin incurred a case of “sophomore-itis” as a freshman (a know-it-all malady). They butted heads a little bit. It smoothed out as Kevin got older. He knew the drill. He knew what was expected. After Colebrook, Kevin went on to a Hall of Fame career across the Connecticut River at Vermont State University–Lyndon.

There were several losses in the semis and then Kevin’s senior year came around in 2000-01. It was Colebrook and Groveton as the favorites, and when the dust cleared on championship day, they were the last two standing. Buddy was going against his good friend, Mark Collins, who he had convinced to take the Groveton job in the late 1980s. Groveton to that point had Colebrook’s number. In fact, the Eagles were in the midst of an impressive run of success having won the last three titles.

“Our history is Mark Collins, the coach, and I are best friends,” Buddy said. “Our families are best friends. We grew up together. Our kids grew up together. We’re always at each other’s houses all the way up through. Now we’re in the final against each other. We’ve got that whole dynamic going. They were going for their fourth.” Another storyline was that in addition to Buddy’s son Kevin playing in his last game for Colebrook, Collins’ son Tod was suiting up for his final game for the Eagles.

Jenness recalls when Kevin and Tod were youngsters, they were fixtures at the after-game get-togethers at one house or the other. “They were funny when they were little. They had a little five-foot hoop and they would be playing basketball. ‘Colebrook’s better than Groveton.’ ‘Groveton’s better than Colebrook.’ They’d be dunking the ball. When they were little like that, when their father’s team lost, they would cry. It was good watching them grow up.” Tod sadly passed away at age 22 in 2005.

Except, of course, now the hoop was 10 feet high and there was an actual state championship on the line in a packed gym. Groveton ended up pulling out a 74-73 win in what Buddy feels is one of the best championship games in New Hampshire high school history. “You couldn’t ask for a better final,” he said. “As far as comeback, as far as drama, as far as excitement.”

Because of foul trouble and a game-ending injury to the indispensable Mike Porreca (broken collar bone), Buddy had to use several players who had not had any meaningful minutes all season. Plus, several key juniors had off games.

The defining moments came in the game’s final 30 seconds. Up one, Colebrook had the ball out of bounds and could not pass it into play. They lost it. They forced a Groveton turnover, but then missed the free throws. The Eagles came down the floor with less than 10 seconds to play, making a pass to a kid situated below the foul line. Buddy recalled the shot: “He turned around, threw up (a shot) underhanded and the ball went in the basket.” Groveton was up one.

Colebrook had five seconds to go the length of the floor to win it, but they couldn’t and they lost. “That was heartbreaking,” Buddy said.

“We basically got the last shot. That’s why we won,” added Collins, who finished his 38th year at Groveton on Thursday with a loss in the tournament quarterfinals at Concord Christian. “It was a big game. We ended up winning that night.”

During that era, Colebrook-Groveton games were standing room only – the kind of crowds that screamed fire-code violation. “The lines started about two hours before the game to get into the gyms,” Collins said. “When that game was coming, that was the talk three days before. ‘Who’s going to win? Who’s going to do this? Who’s going to do that?’ Both teams were very good back then. That’s basically what it was. The place was packed.”

Coming off the 2001 heartbreak, Colebrook still had a very good team returning. Good enough, in fact, to get back to the final and against Groveton, who was now going for its fifth straight title.

Plus, of course, Groveton had Colebrook’s number. Well, at that point, everyone’s number. “They’ll let you know that they’re the champs, for sure,” Buddy said. He recalls the bus ride to Plymouth for the championship. Once they got near Groveton driving south, signs started popping up along the road – “Five in a row.” “One for the Thumb.” Buddy was shaking his head. “There was all this stuff – ‘Colebrook’s good until they get to Plymouth.’ It was like that all the way down. Our kids were looking at this all the way down.”

It wasn’t a bad thing. In fact, Buddy felt they were getting focused. “Not a word was said. The bus was dead quiet all the way down. Nothing,” he said. “I kind of knew we were ready to go.”

The key player that season for the Mohawks was senior point guard Seth Boutin, who had played poorly in the previous championship game. “He knew he was good and wasn’t afraid to say so at times,” Buddy said. Boutin would start running his chops during the season and Buddy would cut him off. “You’ve got to prove it when you get to Plymouth. We’ll see what happens when we get there,” the coach would say.

Buddy recalls before an early tournament game, Boutin did something dumb during a walkthrough. “I just ripped into him,” the coach said. “Ripped into him big time.”

The two knew each other. Once Buddy was finished with his evisceration, it was done and time to move on. As they were getting on the bus, Boutin offered Buddy a few pieces of candy from a big bag he always had with him, just to let him know they were good.

Boutin was absolutely immense in the tournament – the tourney MVP as far as Buddy was concerned. In all three playoff wins, he dominated the three big-time opposing point guards. Groveton and Colebrook had split a pair of tight games during the season, but at Plymouth it was all Mohawks. They rolled to a commanding 71-44 win. “We totally destroyed them,” Buddy said. “We could do nothing wrong. Everything was right there. It was good.”

Buddy felt bad for the kids who graduated the year before, including his son. “That was actually a better team,” he said. “That’s the breaks sometimes. We got the Groveton thing off our backs. We didn’t have to listen to that anymore.”

Colebrook kept it going. They made the tournament again and again, lost in the semis here, a final there. But Buddy knew another title was coming. Colebrook had this great class coming led by Ryan Call. Many were on the 2006 finalist squad as sophomores and a team that lost in the semis in 2007 as Lisbon’s run was coming to a close. The 2007-08 season had the potential to be big. In fact, the whole school year did. That class ended up leading Colebrook to the rare trifecta – championships in soccer, basketball and baseball.

The Mohawks lived up to the hype. They rolled through the regular season with one loss – an early-season setback at home to the other favorite Wilton-Lyndeborough, 78-70. They played the game straight up, not giving anything away. “It wasn’t a bad thing,” Buddy said. “They didn’t get full of themselves.” It certainly took care of the best team conversation. As far as Buddy was concerned, Wilton was the best team until someone beat them. He didn’t want to hear any talk about Colebrook being the best team.

The tournament came. The Mohawks breezed their way to the final. Wilton was the opponent. “Now we release all our stuff,” he said. “All our doubles and different rotations off the ball. They got extremely frustrated.” Colebrook jumped out early and was in control en route to a commanding 68-52 win – their third title since 1997.

But the program was on borrowed time. The enrollment was starting to decline. Fewer boys came out for the team. The commitment level was not what it was. “We always had a core of kids we always told, ‘we don’t want you to be the best in Colebrook. We want you to be the best players in the division.’ That gradually started going down.”

As the talent pool decreased, Buddy felt that he and his staff were coaching at their best, getting every last ounce of effort from those groups in the 2010s. “We weren’t blessed with a whole lot of talent,” he said. “We got them to play. We did stuff we didn’t want to do.”

Up to that point, Buddy’s teams played like a buzz saw. “We’ve always been full court, man in your face, run and jump, double team, halfcourt trap stuff,” he said. “We gradually had to scale back and play a dreaded zone once in a while.”

The biggest change was to run a delay, which they uniquely ran off the high post. It was something no one else was doing. They ran this to keep the score close, to have a chance to catch up if they were behind. Essentially, they did it to have a chance to win.

It was not popular. “Sometimes the kids didn’t want to run it,” Buddy said. “Our fans certainly didn’t want to see it. You just about hear a groan. But if we don’t run this, we’re not winning. I’m here to win. I’m not here to run up and down and lose.”

If the kids did question the delay strategy, Buddy was pretty clear why it was being used. “We’re in a delay because we can’t score points. We can’t shoot. You don’t work (on your game) in the summer.”

That’s kind of how it played out. Buddy stopped teaching in 2016. His former player Ryan Call inherited that post and then took over as AD in 2019 when Buddy got done with that. Call then became the basketball coach when Buddy finally bid adieu to his most cherished position in ‘22. He coached in 2019-20, but took the following year off to deal with prostate cancer. He had 599 career wins. “My whole life I coached,” he said. “I never dreamed of not coaching. The year I took off, when it was all done, ‘Well, I’m alive.’ You know what? I missed it. But I didn’t miss it that much. I promised Ryan I would come back and I needed to come back. I was one win away from 600. I’m coming back.”

But, of course, it wasn’t the same. He didn’t have the same Buddy Trask passion. “It was starting to become a job for me,” he said. “I wasn’t having fun anymore. People said I’d miss it. No, I had my time. I could keep coaching. I didn’t want to do it anymore.”

He got his 600th win. He’d been around long enough that his alma mater, Stratford HS, the first school he coached and taught at back in the 1970s, closed its doors in the 2000s. Its students now go to Groveton. His final Colebrook squad went 7-11 to get that win total to 606. He ended his last season like he began his first way back in 1976 – with a loss. It was to Pittsburg/Canaan who Colebrook had owned for the last quarter century or so. The game had additional juice in that the winner qualified for the Division IV playoffs and the loser stayed home. “It was at our place,” he said. “Everybody likes to go out on top. Losing my last game to Pittsburg/Canaan, that’s how things go. That’s athletics.” It sure is. Of his 45 seasons coaching basketball, his teams missed the pl;ayoffs just seven times – twice at Stratford and five times at Colebrook.

There are plenty of good memories with great players, assistant coaches, parents and principals. He has no regrets. One of his favorite memories outside of the Colebrook bubble was coaching the New Hampshire senior squad in the old Alhambra all-star game against Vermont with Lebanon coaching legend Lang Metcalf. In 1997, he got a call from the New Hampshire Basketball Coaches Organization asking him if he minded if Metcalf, who was retiring, coached with him. “No, I don’t,” was Buddy’s response. “Lang can do it. I’ll step down. I’d just be happy to spend some time with him.”

Metcalf wasn’t having it. He called Buddy and made it clear he was coming along as an assistant and that was that. “The stuff I learned from him,” Buddy said. “The jokes and stories. It was one of the best four days that I had coaching during that time, being around him.”

Kevin showed up for the practices the last couple days. Metcalf took a shine to him. He quizzed him, wondering if he was on the high school team. “Not yet,” was Kevin’s answer. Metcalf then asked if the Colebrook teams made it to the tournament in Plymouth. “We’re there every year” was Kevin’s reply. Metcalf said if they made it to Plymouth, he would come to the game or games to see Kevin play. And he did. “He might have missed one game,” Buddy said. “But he made a point to see him. I’ll never forget that. That was just amazing.”

Buddy left an imprint on the North Country and a legacy at Colebrook. His friend and rival coach Mark Collins admired Buddy’s “attention to the details.” He was also impressed with how Buddy’s former players came back to pay their respects to him. “Whether they played four years ago or 15 years ago, when they come back and see him it’s good to see,” Collins said. “You can just see how much they care about him.”

Collins added about Buddy: “You do it the right way or you don’t play for him pretty much. You do it right and (if you’re not doing it right) you keep doing it until you get it right.”

Buddy and Dale Ramsay have remained close friends 50-plus years later. Ramsay, who lives in Louisville, Kentucky, remembers growing up that even before he got to college it was pretty obvious Buddy was going to be a coach. “He just saw the game at a different level, even in high school. He was three or four plays ahead. It was clear what his path was going to be.”

Gary Jenness was in his first year at Groveton in 1975-76 when Buddy did his student teaching under him in the spring of ‘76. “He was a very good student teacher. He wasn’t very good on Monday morning because he’d go to Plymouth State on the weekend because his wife Mary was a student there and they’d go out. He’d be back around 9 on Monday. Buddy was excellent. You knew he was going to be a great teacher and good coach.”

What struck Jenness about Buddy’s coaching was “he got more out of his kids over the years than many coaches I have seen. He would not have a very good team and they would be very competitive. The one thing he did when he went to Colebrook, he made them competitive. Anytime you played them, you knew you were in for a dogfight.”

Ramsay said when you walk into the Colebrook gym – now the Trask Gymnasium – you see all the banners. “That’s Buddy’s work. They won all those championships in all those sports boys and girls when he was athletic director. That’s saying something.”

Back in 1976, Ramsay and Buddy were watching the sun rise after a night of celebrating a young coach’s first career win at Orford. “All we could think about was that we won one game,” Ramsay said. “You knew, even then, he was going to be successful.”