By Mike Whaley

(This is the fourth in a series on the 2025 NHIAA state championship basketball teams.)

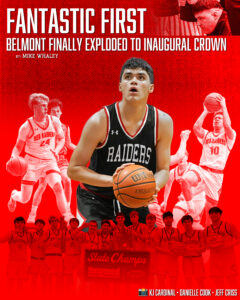

It’s no secret that Belmont High School has a long, painful history of playing second fiddle when it comes to its boys basketball program. Well, that was until this past season. The Raiders finally reached the championship summit in March with a 49-43 win over Kearsarge in the Division III title game at Keene State College. It was the school’s first basketball title in four tries (the three previous runners-up were in Class S dating back to the N.H. basketball Dark Ages: 1970, 1950 and 1949).

It’s no secret that Belmont High School has a long, painful history of playing second fiddle when it comes to its boys basketball program. Well, that was until this past season. The Raiders finally reached the championship summit in March with a 49-43 win over Kearsarge in the Division III title game at Keene State College. It was the school’s first basketball title in four tries (the three previous runners-up were in Class S dating back to the N.H. basketball Dark Ages: 1970, 1950 and 1949).

Coach Tony Martinez can laugh and joke now, but when he took the job three years ago, he knew a substantial task was ahead of him to make Belmont into something it had never been. “For me, coming from my background in Pittsfield,” he said, “I wanted to make it a basketball town. I knew we’d have to start sustaining some winning seasons and ultimately the goal is to bring a championship home. I was really lucky over those first couple of years to get these guys to really buy into it, and we were able to do that this year.”

Over the years, going back to the 1940s, Belmont has had some good teams and great players: Verne Bryant, Ronald Smock, Cliff Greenwood, Chris Lockwood, Nathan Roach, Michael Messier, Sean Newman and Trevor Hunt were just a few of the names to light it up for the Raiders. But team success has been fleeting. “They never really got over the hump to the point where you heard community people saying ‘this is not a basketball town.’” Martinez wanted to change all that.

Although he left his mark in nearby Pittsfield and at Plymouth State, Tony was certainly familiar with Belmont and its basketball history. His mom attended the high school and his uncle was an athlete there in the 1970s.

Two big factors in the Raiders’ eventual success were exactly that – big. When Keegan Martinez and Anakin Underhill came in as freshmen, they already had size and a clue or two about how to use it. They were also very familiar with each other having been teammates since they were in fifth grade. By the time they were seniors, they were the centerpieces on not only the biggest team in the division, but the squad with the strongest defense and most explosive offense. Underhill will take his 6-foot-6 frame to NCAA Division I Sacred Heart University next year as a baseball pitcher, while the 6-5 Martinez will follow in his father’s footsteps and play basketball at Plymouth State University.

When Tony Martinez replaced Jim Cilley in 2022 as the head coach, he knew he had his son and Underhill as experienced sophomores along with a talented senior class. But he still had a lot to learn.

“As a rookie coach, my first year I came in with the mentality, I’m going to teach them how I played,” said Tony, who was a star player at Pittsfield High School and Plymouth State, scoring more than 1,000 points at both schools. “I’m going to change these guys. We’re going to play this style. It wasn’t that I did it on purpose. I was kind of close-minded to what we had for individual skill.”

Tony got some great advice from close friend and Pittsfield coach Jay Darrah. “When I got the job, he said ‘Tony, one of the biggest things you’ve got to understand as a head coach especially with your playing background, is the kids these days aren’t going to see the game the way you did.’”

It took a while for Darrah’s words to sink in. “That first year I kind of coached it, I wanted the team built in my style, rather than looking at them and taking them at what they could offer and putting it together.”

The team didn’t improve or come together. “We had some injuries and typical things that teams face,” he said. “But we weren’t built to face adversity yet. Even me as the coach. I wasn’t built to face adversity yet.”

A big learning curve for Tony was coming in as a new coach who had inherited seven or eight seniors. “They had come off a couple of up and down seasons and I was trying to get them in that winning mindset,” he said. So here was Tony with his new ideas and you had a group of seniors who were winding up their high school careers and thinking about their futures. “When I first took the job, I never understood how a player could think that,” he said. “Now I can see it and understand it. It’s hard to get them to buy in.”

Tony did not have a problem with the seniors as people. He thought they were fantastic. He is still in touch with all of them. “It was hard to put it all together in the time frame we had. One thing I tell that senior class is I wish I had two more seasons with you. If we had two more seasons together, I think that team would have been the one to put the banner up.”

That first year the Raiders started strong, but didn’t end that way. They went 9-9, earned the No. 9 seed in the D-III tournament, losing in the first round at Conant, 56-44.

“Those guys were older,” said Underhill of the seniors. “Me and Keegan were younger. Those guys were in their own separate group. I was friends with most of the guys. It wasn’t super tight like it is now.”

After that first season, Tony sat down and wrote out what the strengths of the team were. “Obviously it was no secret to anybody, we needed to build the team around Keegan and Anakin,” he said. “They were our two bigs. They were our two best players at the time. I knew we had other good returning juniors, players like Michael Collette and Brady Thurber. We had some other sophomores: Wyatt Carroll and Brady Fysh. I knew we could build something solid around those guys. We had a really good freshmen class coming in with Brody Ennis, Owen Viar and Wyatt Bamford. I knew we had a lot of talent, a lot of pieces. It was just going to be up to us to find a way to put it all together. It was rough at first. I refused to call it a rebuilding year, even though it was.”

The Raiders took their lumps early, starting the 2023-24 season with a 3-4 record. “We started hearing those questions. ‘Is this the right lineup?’” Tony recalled. “All the stuff that happens when things aren’t looking great. I knew that we were kind of pointed in the right direction. But we were going to take our hits.”

The turning point came in game number seven at Saint Thomas Aquinas, a 68-35 waxing. “We had some infighting and stuff like that,” Tony said. “We were down in the locker room at the end of the game, and I lost my mind. I basically told the guys how I felt in a colorful way.”

Immediately after he finished his tirade, Tony thought: “Oh boy, I don’t know if I’m going to be here next week.”

There was a senior on the team named Hutch Haskins. Tony said he wasn’t the most talented player, but he gave it his all. “He was probably one of the greatest high school leaders I’ve ever seen in anything he’s done,” Tony said. “I remember it was kind of somber after that. Everybody was processing what I had just said, including myself. I’m walking out of Saint Thomas and I see Hutch standing on the staircase before the bus. He comes up to me and gets right in front of me. ‘Coach, I’ve got your back. We needed to hear that.’ I was immediately like ‘wow.’ That’s amazing. I knew with him (Hutch) he would relay to the guys or any guys who might be on the fence about it. From that point we really began to understand the work that needed to be done and what we had to do with our attitudes and everything to start turning the corner.”

Belmont went on a huge run from there, winning eight of their final 11 games to end the season at 11-7. In the last game of the regular season, they won a huge game at Gilford, 50-34, with a bunch of playoff implications on the line. It was the first time in a half dozen years or so since Belmont had won at Gilford. “It was crazy,” Tony said. “I remember us celebrating like we had won the state championship. That’s when I knew we were taking a step forward to win a game with all those implications before a packed house with all those young players.”

The Raiders earned the No. 7 seed, which meant a first-round playoff game at home. There they beat No. 10 Fall Mountain, 52-36, to advance to the quarterfinals for the first time since 2017. The season ended at eventual champion Saint Thomas, 67-50, a game that was separated by one point at the half. “I remember the Saint Thomas game, specifically,” Underhill said. “They were really good. They’ve been in those situations. We really weren’t that experienced. I wasn’t ready for that level of basketball.”

Still, for Tony, it was a step forward. “I knew after that with everyone we had coming back, we had an opportunity to make this season special if we could put the work in,” Tony said.

Another factor that would come seriously into play going into the ‘24-25 season was the return of junior Treshawn Ray, a guard with some serious upside. Looking back, Tony regrets how he handled Ray during his first year. “One of the biggest mistakes I made with Tre as a freshman, I tried to change his style of play and make it more conservative,” Tony said. “As a freshman, I thought I was doing him a favor.” Tony recalls calling Ray over and going “‘No, Tre, you’ve got to do this. No, you’ve got to do it this way.’ I think I kind of handcuffed him and made him not comfortable in the way he played.”

Ray is from a split family. In 2023, he moved in with his dad in Boston and played part of his sophomore season at Reason Prep before leaving the team and eventually coming back to Belmont to live with his mom. His intent was to return to the team to play for his junior year. “When I coached him this year, I don’t know how many times I called him over this season: ‘Go do your thing. Go play your game.’”

Tony remembers Ray reaching out to him at the end of last summer, saying he wanted to come back and get back on track. Ray was homeschooled, so that piece had to be ironed out in conjunction with him playing sports for Belmont. It eventually was.

Tony recalls a conference call with Ray and his mom, Keegan, Tony and assistant coach Scott Ennis. “To sum it up, I told Tre exactly what I expected – the dedication, the commitment to the team, the leadership” Tony said.

Ray was glad to have everything out on the table and glad to build a bond with his coach and his team. He said that conversation allowed him and Tony to “build a bond off the basketball court so that when we get to the basketball court we already have a good feeling about each other. Before the season started, we’d text, we’d talk, we’d keep it short. We really built the connection.”

Before Ray returned, Tony figured the team was one guard away from being a serious contender. “I had a younger guy, but he wasn’t quite ready,” the coach said. “(Tre) was the final piece to the puzzle. We had size, wings and rebounding. I knew we could play defense. We just needed that one extra piece. When he came in, he fit right into that.”

What really caught Tony’s eye was how the Belmont players reacted to Ray’s return. In choosing captains, Tony had a rollover captain, which was Keegan, and then had the team vote for the other two captains. They voted for Underhill and Ray. “His turnaround in maturity from his freshman year to the time coming in here this year, it was night and day,” said Tony. “The guys saw that and voted for him. I think it was a unanimous vote. It showed me and my staff just how valuable a leader he was because the guys believed in him already.” Belmont now had everything in place, on paper, to make its run. The question remained, would they be able to do it?

The Raiders came out ready. In their second game they hosted and beat Gilford (61-45) in a big rivalry game before a packed house. “It was a playoff atmosphere,” Tony said. “For us to win that, that was the first benchmark. That we could win a big game early, that showed me that we had big-game capability.”

The next challenge was the Mike Lee Holiday Basketball Bash in Farmington. There is the potential to play a lot of basketball. “If you’re a good team, you play five games in five days,” Tony said. “I wanted that for this team. We needed to keep building that experience.”

The Raiders ended up playing a very competitive schedule. Their first four wins were over Raymond, a top-10 playoff team in D-III; a solid D-II squad in Kennett; eventual D-II runners-up Sanborn and a strong D-IV team in Portsmouth Christian. “We were seeing some different defenses and some different things that were kind of exposing us,” Tony said. “For me as a coach, I was seeing what we had to work on.”

In the championship, Belmont faced a very solid Division II playoff team in Coe-Brown, coached by the legendary Dave Smith, who had coached against Tony when he played for Pittsfield HS in the 1990s. “You’re never going to see a more disciplined or better-coached team than a Coe-Brown team with him at the helm,” Tony said. The Raiders played without Underhill who had an arm injury. With a baseball future looming in college, they did not want to risk further injury, so the big guy had to sit. It gave Belmont the chance to play some younger guys in a big game before a packed house. Coe-Brown won in overtime, 66-64.

Tony was ecstatic. “I went into the locker room and for the first time in my coaching/playing career, I wasn’t upset (after a loss),” he said. “I wasn’t sad. I looked at the team. They were really upset. I was really taken with how the team valued a Christmas tournament championship.”

Tony then asked the team a simple question. “Do you want to feel this feeling again? And they are all like ‘No. Not at all.’ … I said I would rather see you feel this way now – all of us feel this now – than on March 1. They all bought into that. That was one of the first steps in us taking that giant step forward.”

The Raiders came back from the holiday break, adding four more wins to their perfect D-III mark to improve to 7-0. Then they lost at Campbell by nine points, 69-60, 10 days after beating the Cougars by 19. “It was our worst game of the season,” Tony said. “We had like 24 turnovers.” Campbell hit Belmont with a zone and it totally stumped them. It was another good lesson learned. “OK, now we know what everyone is going to do against us,” the coach said. “I know as a coach that every coach in Division III was going to be on (coach) Justin (DeBenedetto’s) email that night. ‘Can I have your film?’ I knew we were not going to see man-to-man the rest of the season.” It’s worth noting that Belmont allowed 60 or more points only twice all season – both losses.

Underhill recalls a conversation he had with his dad before the season even began. His dad essentially said it was very hard to go undefeated and if you did there was a big target on your backs. “‘You guys need to lose one game and that will take some pressure off you guys,’” Underhill recalls his dad’s words. “‘And that will help you win the championship.’”

Underhill felt there was merit to those words, although he added, “I didn’t plan for us to lose. I wasn’t afraid of losing because I knew guys had to learn and I had to learn too, and we could do better from that.”

Belmont had little time to lick their wounds as Saint Thomas was due in town two days later. Tony admitted he was nervous. “It’s hard for high school kids to have an emotional loss and have two practices and then go right into another big emotional game against the defending state champs with arguably the best player in the division (Cole McClure).”

Heading into the fourth quarter, the Raiders found themselves down nine points. They came back and won by two, 50-48. “This showed me how much desire these guys had and how much they wanted to win a championship,” Tony said. “They were willing to do what it took to win.”

Belmont finally had complete buy-in from everyone. “Up until that point, I had a few guys that had more significant roles the season before and were playing less,” the coach said. “They weren’t causing a problem, but they were doing ‘Hey coach, what am I doing wrong?’ We got a lot of that. We had to do a lot of open explanations of what we were doing to players. After that Saint Thomas game, I rarely had to talk to players about their roles. They started accepting everything.”

Underhill remembers during the season people coming up to him and mentioning how great the team was doing and not to mess it up. “In my mind, I would say ‘four quarters at a time and we’ll see what happens,’” he said. “We can’t say anything now. We’ll just play our hardest and see what happens.”

The Raiders wrapped up the season with a 17-1 record to earn what was believed to be the first No. 1 seed in program history. Going back to the summer, Belmont had adopted the term “stacking” from assistant coach Scott Ennis. “We wanted to stack our positives,” Tony said. “Learn from our mistakes, stack our positives. Stacking the positives, you keep building towards your goal.”

What Tony took from stacking was to take each game and break it down into pieces. “I used baseball a lot as an analogy because I had a lot of baseball guys on the team,” he said. “One batter. One strike. One inning. We kind of looked at games from the tail end of the season in preparation for the playoffs. OK, each game is four eight-minute games. We’re going to look at each quarter as its own eight-minute game. We’re going to win each eight-minute game. You win each eight-minute game, you win that night. We started getting the guys really mentally prepared that way. Don’t worry about what’s two quarters ahead or what’s behind you. It’s kind of a variation of one (minute, quarter, game) at a time.”

If the games were close, they would break those quarters down to minutes. They used that time element in practice. “When we started practicing, we really went live and put time on the clock and we practiced what we needed to do in those situations. We knew that if we needed to do something in a game, being down or being up, we knew what to do and to understand the game and time and score. We really focused on that as we prepared for Fall Mountain in the playoff run.”

The Raiders earned a first-round bye, which meant they would host a quarterfinal game against the Fall-Mountain/Raymond winner, which was Fall Mountain. Tony would have preferred to play a first-round game instead of having the week off. “You hear all the time that the week off is difficult,” Tony said. “No matter how good your team is, how talented they are and how prepared (they are). Not having that live action in the middle of that is tough.”

Underhill agreed. “That bye week wasn’t settling well with any of us,” he said. “We really just wanted to play. I remember that week. It was torture.”

Sure enough, Belmont came out flat. It took a little while to shake the cobwebs off, but they eventually did win going away, 72-50. Four players reached double figures, led by Ray and Keegan with 18 and 17 points, respectively, while Thurber (11) and Underhill (10) also chipped in.

That meant the Raiders were making a rare trip to the semifinals against the defending state champs from Saint Thomas at Bow High School. “The guys were generally excited about it,” Tony said. “They were not nervous. We’re going to be OK. We’re going to be fine.”

Until they weren’t. At halftime, Belmont found itself down by nine points. It was tied at 23-all, but the Saints went on a 10-1 surge to end the frame up 33-24 – the same margin they had led by during the regular season after three quarters. Tony recalls the team was gathered in a classroom and Tre, Annakin and Keegan were all there. “They were so positive. ‘We got this. We’re going to be fine.’ We’ve got 16 more minutes. Two eight-minute games.,” the coach said.

Belmont knew they weren’t going to shut down McClure, the two-time D-III Player of the Year. Instead, they focused on limiting STA’s next two top scorers in Anthony Settineri and Finley De Tolla. The two had combined for 33 points in a 74-66 win over Campbell in the quarterfinals while McClure tossed in 32.

“Look, shut them down,” Tony told his team. “Don’t let them get anything easy.” It paid off as the defense held the duo to 15 points between them. McClure had 34, but he had to work for them. One adjustment Belmont made at the half was to double McClure on the inbounds pass after a made basket. The Raiders learned that if McClure was allowed to walk the ball up the floor unchallenged, eight out of 10 times something good happened for Saint Thomas. “So the little trick was to make McClure work for it to get it on the inbounds pass. That was it.”

Tony said: “Just a little change. We were the best defensive team in Division III along with the best offensive team. During the season we gave up under 100 second-chance points with our rebounding capabilities. To me that’s one of my favorite stats. We did not let any other teams get any second-chance looks. For the most part it was one and done.”

Belmont outscored the Saints 21-8 in the third quarter to take the lead for good going into the fourth, 45-41. They had all the momentum after Ray hit a long 3-pointer at the buzzer to end the third. The final score was 69-53. Keegan and Ray led the attack with 23 and 22 points, respectively, and Underhill added 12.

The Raiders were on the threshold of history. They were playing in their first championship game in 55 years looking for the program’s first title. “Now we turned our focus,” Tony said. “Let’s win this thing. Let’s put the cap on it that we want to put on it.”

Their opponent in the final at Keene State was deceptive No. 3 seed Kearsarge, coached by one of the division’s grand masters – Nate Camp. “He puts much effort into watching film and studying games,” Tony said. “His coaching staff is excellent. They put a lot of effort into preparing their team.”

The one thing about Kearsarge is they were not big, which could make you overlook them. “I was underwhelmed with Kearsarge’s size,” Underhill said. “It showed that these guys were beating up on some teams and they’re not really that big. We’re getting into the game and these guys are crafty. They were better than I thought they would be. ‘Wow, this is going to be a dogfight.’”

Keegan felt Kearsarge was very physical. “I remember cutting to the hoop and there would be two guys bumping me off my cuts every time,” he said. “They were just a scrappy team. Theyworked very hard. We just had to match their physicality with getting rebounds and boxing out.”

Tony added this about the Cougars: “They are tough. They don’t give up. They don’t quit. They are crafty in what they do. They hit shots. How did they hit that? They deserved to be there. I can see why.”

Belmont started strong and took a comfortable lead into the locker room at the half, 30-19. “I was thinking we can really blow the lid off this thing,” Tony said.

But that was not the case. Ray got the lead to 13 (32-19) at the outset of the third. However, Keaarsarge’s full court press gave Belmont some trouble, more so than it should have. The Cougars worked their way back into the game, also getting help from the Raiders’ inability to hit foul shots (2-for-14 in the second half). Eventually they cut the lead to 44-41 with 2:35 to play. Key putbacks by Underhill and Keegan helped Belmont to hold off the Cougars to secure the program’s first state title, 49-43. Keegan ended with 15 points and 17 boards, while Ray had 15 points and five assists. Underhill added 12 points and 10 rebounds. The Raiders enjoyed a 35-22 advantage on the glass. According to Tony that was the difference in the game. They limited Kearsarge to one second-chance bucket. Eli Whipple paced the Cougars with 15 points.

“I had a coach tell me when I was little, two things win basketball games: Rebounding and free throws. Thank god we could rebound,” Tony said.

It was no surprise that Belmont’s Big Three led the team during its playoff run: Keegan and Ray averaged 18.3 points per game during the playoffs, while Underhill tossed in 11.3 ppg. It was a similar story during the regular season. Keegan was tops at 18.2 ppg, followed by Underhill (14.8) and Ray (11.7). All told, counting the regular season, the holiday and state tournaments, the Raiders went 24-2. Keegan and Underhill were named to the D-III All-State First Team, Ray made the second team, and 6-3 sophomore Brody Ennis was picked to the All-Defensive Team. Tony was named D-III Coach of the Year.

It was the ultimate coaching joy, winning a program’s first-ever title and doing so with your son. “I was lucky to be on the bench with Jay Darrah when he won it with Pittsfield in 2018 (the Panthers’ first title),” Tony said. “I got to see him win one with his son (Cam). And then I win with Keegan. It’s something that I’ll have forever.”

The father/son dynamic is not something that always works when it comes to coach/player, but like the Darrahs, Tony and Keegan made it work. It helped that Tony had coached his son before on AAU teams. Tony also felt it was integral that Keegan had played as a freshman so that when Tony took over during his sophomore year, he was already established as one of the team’s better players. “With Keegan I always knew that he was going to do what he needed to do to be the player that he needed to be,” Tony said. “I never questioned that. Was I sometimes harder on him than other players? Yeah. I don’t care what coach talks to you and tells you differently. You’re always going to be a little harder on your kid. That’s just the way it is. There’s no sugar coating it. Even at times that I didn’t want to be, I’d say something. It’s the way it is. Keegan also knew that.”

There were times early on in his coaching tenure that Tony would tell Keegan beforehand that he was going to be getting on him at practice. “I need guys to see that you’re not going to be handed anything,” Tony said. “I never handed him anything. Keegan, honestly, earned everything he got.”

By the time he was a senior, Keegan had developed his game to the point where he was more physical, which allowed him to do more things. “”I was getting in the post to make moves on guys,” he said. “I was able to body people to get those second-chance points. I feel my 3-point and mid-range shot got a lot better.” As a captain, he became more engaged as a respected leader of the team.

Because the dynamic of the team changed with the return of Ray and the emergence of sophomore Brody Ennis, some of the older players saw their playing time diminish. Tony tipped his hat to Carroll, Colette and Fysh. “I was so proud of them as players and young men for accepting their roles,” Tony said. “Because not many guys can take a step backwards and be OK with it. All those guys took steps back minutes-wise because their roles changed. … For them to be positive and to accept the things that they accepted and play the way they played, we don’t win a championship without those three players.” The proof is, indeed, in the pudding.

Whaley can be reached at whaleym25@gmail.com