By Mike Whaley

Note: First in a three-part series on the state’s 2,000-point high school basketball scorers.

There was a time when it seemed like, well, it was raining 2,000 points.

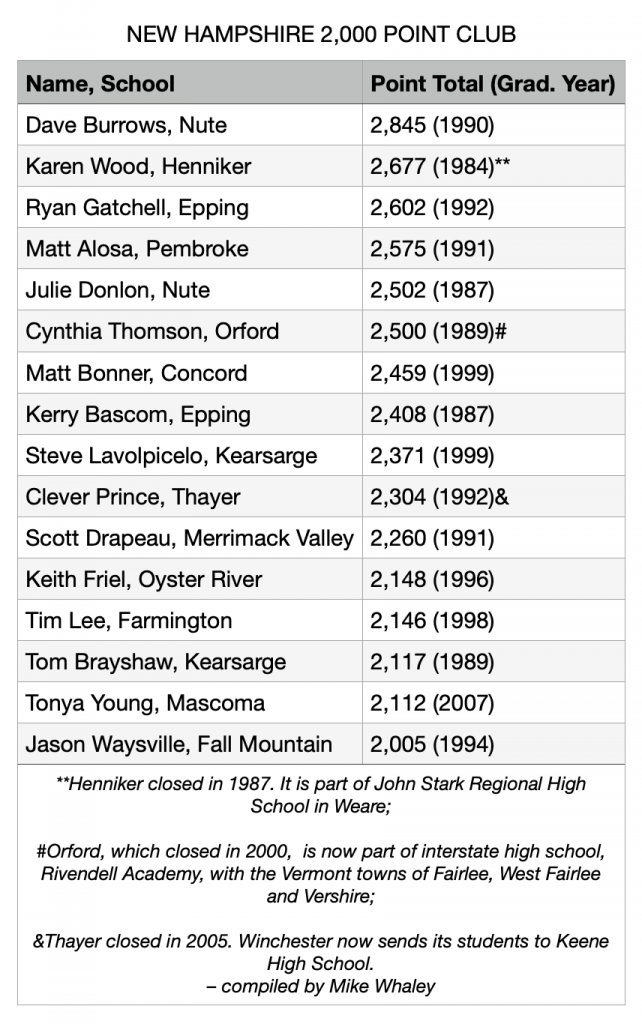

From 1983 to 1999, 15 of New Hampshire’s 16 double-century point scorers reached that milestone (see accompanying list). One has done it since.

While we may see 2,000-point scorers at some point in the future, there is simply no way that special basketball era will come close to being replicated.

THE GIRLS GOT IT STARTED

There is a symmetry to the list.

The first four players to reach the milestone were all female, and the last to hit the mark in 2007 was also a girl (Mascoma’s Tonya Young). In between, 11 guys hit the mark.

Those first four women all played in Class S/Division IV, and all played in the 1980s.

Henniker’s Karen Wood was the first player in N.H. to hit 2,000 in 1983, and she remains the highest scoring female with 2,677 points, and is second in N.H. overall. Only Nute’s David Burrows has scored more (2,845).

While her career was winding down at Henniker where she led the team to four consecutive Class S championships (1980 to 1984), Epping’s Kerry Bascom and Nute’s Julie Donlon were just getting started.

As was the case then and still holds true today, athletes in Class S/Division IV are allowed to play varsity high school sports in seventh and eighth grade. Wood, Bascom and Donlon, as well as Orford’s Cynthia Thomson, all played varsity as eighth graders.

While Donlon and Bascom had a long history playing against each other, they did meet up with Wood at least once – during the 1984 Class S tournament. Bascom’s Epping team was locked in a close game in the quarters down two points, but with 45 seconds to play Bascom injured her ankle and had to leave the game. Henniker was able to hold on for the win.

Henniker met Nute and Donlon in the final, claiming an easy 74-38 victory.

There is no doubt that these girls benefitted from an extra year to reach 2,000 points. But it should be noted that all five females who hit the milestone went on to play at the NCAA Division I level. Bascom is generally regarded as the state’s greatest female player having taken her college game to UConn where she played for Geno Auriemma as his first big star.

At the time, Donlon and Bascom not only played against each other, but also with each other on AAU teams, at a time when that concept was in its infancy. They played and more than held their own with girls from bigger schools, like Nashua with Celeste Lavoie, Becky Shrigley, and Stephanie Byrd.

“We just played together for five years. … We were playing with all those girls, so we knew we could play,” Bascom told Seacoastonline in 2021.

In fact, the first two years that Bascom and Donlon played AAU, there was no New Hampshire team. They traveled to Massachusetts to play on a team made up of N.H. girls, until Mass. said enough is enough. They had to form their own N.H. team, which happened with Nashua’s John Fagula as the coach

It was a competitive rivalry between the two women.

“We were friends, but we were competitive when it came to Epping-Nute,” Donlon told Seacoastonline last year. “When we got on the floor, that was over. The gym was always packed. Standing room only.”

Bascom said they scored their 1,000th career point a game apart. Ditto for their 2,000th point.

BOYS GET THEIR GROOVE GOING

By the end of the 1980s, the boys started getting in on the act. Tom Brayshaw, who starred at Kearsarge for Marty Brown, was the first to hit the mark in 1989. Kearsarge was well known for its fast-paced style, reminiscent of the Loyola Marymount teams of that college era coached by Paul Westhead that routinely scored over 100 points and led the nation in scoring three years running.

Brayshaw was the state’s recognized top boys’ scorer for all of 10 months. He surpassed 2,000 points in February of 1989, and in December of that year, Burrows passed him, and still holds the record to this day.

It was a deluge at that point. Nine more boys followed until 1999.

“What it is, you had a perfect storm,” said Pembroke’s Matt Alosa, who scored 2,575 points, the most by a four-year player. “You didn’t have the social media scenario you have going on now. Kids only play when there’s some organized event. They no longer live in the park. I lived in the park, every day, 7-8 hours a day.”

That was a common denominator. Players of that era had a passion for the game at a young age, and spent endless hours on the court. They not only played various forms of pickup games, but also worked individually to hone their games.

“When I was a little kid growing up – spring, summer and fall – I was in the park every day playing,” said Alosa, whose primary hot spots in Concord were the courts at Memorial Field and Fayette Street Park. “I got dropped off there. I wasn’t allowed to leave, but I could stay there anytime I wanted to, all day.”

Alosa said he knew when people were going to show up for games, whether it was full court or 3 on 3.

In the winter, he tagged along with his dad who was a high school coach at Bishop Brady and then Franklin at the time. “I can remember practicing when I’m 6, 7 and 8 years old,” Alosa said. “I practiced with the freshmen and the JVs, but I was in the gym for freshman, JV and varsity practices all day long.”

He recalls at age 13 playing with a bunch of college guys who he’d met in the park in a men’s league at the Concord prison.

As he got older, Alosa had a group of kids he played with. “I can remember being with my group of guys going from place to place to just play and find pickup games,” he said. “I was working out all the time. Sometimes pickup. Sometimes shootaround. I’d eat a sandwich under the basket with a Gatorade.”

Farmington’s Tim Lee recalls a similar upbringing when his dad was the high school coach. “I grew up in the gym at the start of my father’s career,” he said. That is where he developed his confidence and competitiveness.

“Part of that was growing up in the gym,” Lee said. “When I was in sixth and seventh grade, junior high, I was doing drills with the varsity players. … Growing up in a small town, I had the advantage of being able to run with the varsity guys and being around their summer leagues. I was always shooting at half time (of JV or varsity games) and after the games.”

Keith Friel also had a dad who was a coach, but his story is certainly different. Gerry Friel coached the University of New Hampshire men’s basketball team from 1969 to 1989, and the Friel family continued to make their home in Durham, even after Gerry finished coaching.

In addition to being able to walk to Lundholm gymnasium every day to play pickup, the Friels spent eight weeks of their summers in Exeter where Gerry ran the Phillips Exeter Academy basketball camp until Keith’s eight-grade year.

“I was born there during camp,” Keith said. “There wasn’t a ton to do so we did non-stop gyms. We did camp every week. And the girls’ week we would help out with officiating, running the scoreboard. We had a ball in our hand at all times. It was an overnight camp. They’d start at 8 in the morning and go until 9 at night. Since you’re around that, you’re around the coaches non-stop, picking up (things) from lectures from every angle. I was always asking questions.”

Keith recalls always playing against the UNH players when he was in high school, including Alosa and Scott Drapeau when they showed up in the mid 1990s. “They’d call or message with a time and we’d be there,” he said.

That was a good challenge when he was younger playing against athletes who were bigger and stronger. “So how are you going to be able to stay on the floor to impact the game?” he asked himself. “So you start problem solving at a young age. I better box this guy out or I’ll have a grown man yelling at me. We have to win this game to stay on the floor.”

But that was a great way to get better. Alosa, Friel and Lee all played against older players, which is humbling but helpful in the long run.

Dave Burrows had two older brothers growing up in Milton. Steve and Scott were stars at Nute. Steve started on the school’s first hoop championship team in 1980 and went on to score 1,000 points, as did Scott, a 1986 Nute grad. “They let me play pickup with them,” Dave said. “My brother Steve would take me over to Farmington and we’d play pickup with the Muchers. That’s how I started understanding the game as far as keeping your mouth shut and playing and having fun.”

The pickup game toughened Burrows up, playing against bigger and older players. “That’s how you really learn,” he said. “I always tell players, 3 on 3 is the best way to learn basketball. You’re moving, you’re understanding how to pick, spacing.”

As he got older, he was always in search of a good game of pickup. “In Milton, I would literally go to the church,” Burrows said. “If there wasn’t a pickup game, I’d go to Rochester. If the pickup was bad there, we’d go to York (Maine) and play King of the Court. I could drive around Farmington, Rochester and see players shooting outside. You don’t see that today. No 3 on 3. No 4 on 4. No King of the Court. That’s how you learn.”

While Burrows had his brothers to push him, Keith Friel had his brother Greg, who was a year younger. “He was as hard a worker as I’ve ever seen,” Keith said. “I’d wake up in the summer and love to see that he was already dribbling and shooting and getting some drills in. I wanted to be the first one up.”

Tim Lee’s older brother, Josh, was essential in Tim being able to come into high school and have an impact. Josh Lee and Shaun Lover were talented, savvy senior guards, whose presence made it easier for him to play. “They helped a ton,” he said. “Especially with the attention that they drew. That allowed me to spot up and shoot. I didn’t have that luxury the last three years.”

Lee scored 33 points in his first varsity game, which gave him confidence going forward.

Burrows had those good Burrows genes when he was younger, which allowed him to play varsity in eighth grade. He grew six inches in seventh grade, so he was a skinny, but coordinated, 6-foot-3 in eighth grade. However, he could score from the get-go, regularly dropping 20 or more points. Coach Phil Mollica defined roles in the preseason, and Burrows’ role was to score. Everyone understood that. “Egos were checked at the door,” Burrows said.

Alosa recalls as a freshman beating out a senior who had started for two years. “I had to earn that spot, but it was a no-brainer,” he said as he went on to score over 400 points as a frosh. “It takes a courageous coach to say I’m going to play this kid over a senior. A lot of coaches are just against it. No matter how much better a kid is.”

Another factor, beyond being physically mature enough to play and score as a freshman or an eighth-grader, is that you have to remain healthy for four or five years.

Also, the 3-point shot, which was adopted at the high school level before the 1987-88 season, has helped. Friel and Lee certainly benefited from that shot, and might not have reached the 2,000-point club without it. It helped others as well.

It should be noted that Donlon, who went on to set 3-point shooting records at UNH, played in the era just before the 3-pointer came to high school. She scored 2,502 points without the three. Had she had it, then one can speculate that she would have passed Wood and challenged Burrows..

Donlon and Burrows are the only 2,000-point scorers from the same school to play at the same time at some point. Donlon graduated in 1987, so Burrows got to see her game during his first two years on the Nute boys’ varsity team.

“I loved her game,” Burrows said. “I learned a lot from Julie. She was very generous with her court. She was willing to help. Her ball handling was top notch. Passing and ball handling, she had it all. She was really good. She’s the best basketball player to come out of Nute, in my opinion.”

One point that is made by some of these prolific scorers is that getting to 2,000 wasn’t something they necessarily aspired to.

“It was never on my mind,” Lee said. “I was just trying to be a good teammate; trying to win a state championship and putting a banner on the wall. That seemed to be more significant growing up in that program.”

The same for Friel. “I think I was ultra-competitive,” he said. “That led to not just scoring points, I wanted to win. … The priority growing up as a coach’s son was never the amount of points. It was always ‘who won the game?’”

He added, “My end goal was never who had the most points. Obviously, I loved scoring. I still do to this day. I love shooting and hearing that net snap. That doesn’t change – the satisfaction of that.”

If you look at the 2,000-point club list, of the 16 players on it, 10 experienced at least one state championship, and five were on multiple title squads. “It was always what can we do to win the game,” said Friel, who played on back-to-back Class I championship teams at Oyster River (1995 and 1996).

Another important piece to consider is the evolution of AAU ball. When many of these 2,000-point players were in the game, AAU was in its infancy. In fact, there was just one team for a while for boys and girls, and the best players played on those teams. That’s not like today where there are multiple teams, and you do not see the state’s best together on one team. In some cases, the better players are competing with elite teams from out of state.

Case and point was an AAU team that Alosa, Burrows, Gatchell and Drapeau played on in the early 1990s and late 1980s coached by Frank Alosa.

Alosa recalls at age 13 going to a tryout for the AAU team at Dover High School. All three courts were in use with kids all trying out for the one team.

“That’s what it was,” Alosa said. “We had a group of 12 or 13 guys that went to the nationals and finished sixth out of 100-plus teams at Disneyland.”

Similarly in the late 1990s, Frank Alosa coached an elite N.H. AAU team with Bonner, Lee, and Steve Lavolpicelo from the 2,000-point club, as well as some other big names like Billy Collins, Marshall Chrane and Mark Yeaton. “That team was loaded with Division I and 2 talent,” Lee said. “We finished in the top-eight in the country in Florida.”

Players of that era did not go to prep school at the rate they do these days. Burrows said he has a chance to play with Alosa at Pembroke Academy after his sophomore year. “I just made the decision I was happy in Milton,” he said, which worked out as he led Nute to the 1990 state title in Class S. “To be totally honest, I figured if I transferred, I’d lose my girlfriend.” Burrows has been married to his “girlfriend” (Lisa Dube) for 26 years.

After his sophomore year, Alosa came close to going to DeMatha Catholic High School in Hyattsville, Maryland, a prominent national basketball power. “I started getting a lot of attention,” Alosa said. “I went to the nationals my sophomore year. I played really, really well. The letters started pouring in. We decided I didn’t have to go.”

Bascom contemplated going to a bigger school midway through her Epping career. She was courted by Class L schools in Exeter and Dover (where her dad played), but in the end decided to stay true to her hometown.

Friel had an offer to attend Phillips Exeter Academy on scholarship after eighth grade, but his mom said no to that, not wanting her son away from home at a young age.

Looking back, Friel wonders if maybe he should have gone to prep school for his senior season. “I wasn’t challenged very much from a competitive standpoint,” he said. Although Oyster River defended its championship, Friel recalls many, many blowouts in which he was lucky to play half the game. He felt it stunted his development to some degree. But it still felt good to stay and help Oyster River win another title. Winning, in Friel’s mind, has always been the end goal – not the points.

2,000-POINT CLUB WEIGHS IN ON THE GAME TODAY

Alosa, Burrows, Friel and Lee have their own opinions on why it is harder today to get to 2,000 points.

Here are some of the factors: Kids play less pickup and more AAU. Some of the better players opt for prep school. The game is slower. Kids lack fundamentals. Social media.

“When I played, players were playing,” Burrows said. “What I’m watching today is too structured. You go to a team. You travel around to tournaments.”

“There’s a significant decline in recreational pickup,” Lee said.

“I just don’t see (pickup) anymore,” said Alosa, who coached at his alma mater for 10 years, winning two state championships. “It’s a skilled event. It’s a motor skill that you have to do over and over again. You have to log the hours. If I play seven hours and you play one, I’m going to be better than you in a year.”

He added, “The organization for good or bad is that kids don’t do anything unless their parents bring them to practice for an hour and a half a couple of nights a week. That’s basketball.”

“It has to be organized,” said Friel, who runs Friel Basketball, offering team and individual instruction. “You’re playing in your grade and age group. You’re playing so many games year round. They’re playing all these games. When are they working on their skills? You have four or five games and maybe one or two practices. When are you working on your weaknesses?”

He thinks kids are not taught much about fundamentals. “Everybody has a team,” Friel said. “There’s a lot of dads coaching at a young age.”

Burrows agrees. “I think a lot of the skills just aren’t there,” he said.

In the 2,000-point era, it was more likely that the best players would play together on one AAU team. Not so today. With so many teams, the talent is spread out, or even gone to play out of state with elite regional teams.

Top players are also more likely to go to prep school today. It’s not uncommon to see good players competing one, two or three years of high school and then going prep, often reclassifying.

Social media may have also played a role as a distraction. Lee said you have young kids before they get to high school, ages 12, 13 or 14, have more pressure to look good for the highlight clip. “Technology becomes a distraction,” he said. “Video games. Cell phones.”

The pace of the game has changed. Games are slower and the scores are lower. As an example, if you added the four 2021 boys championship games together you get a total of 313 points. It is the lowest combined point total for the four championship games since the NHIAA went to four divisions for the 1963-64 season. One team scored more than 50 points, while four scored 40 or more and three scored in the 30s. The overall average was 39 points.

“A lot of coaches like to control the environment more,” Alosa said. “I think some of that has to do with the level of confidence in talent.”

“But with no shot clock and lack of fundamentals coaches think ‘I’ll take my chances. We don’t have as much talent right now. Let’s work the ball,’” Friel said. “You’re seeing these possessions of a minute and a half. I don’t fault the coaches. They’re trying to win. But 4-2, 8-4 quarters. That’s ridiculous. How much fun is that?”

In his era, Lee said the 2,000-point scorers and their peers managed the game clock. “There was little time between possessions,” he said. “The ball was being taken out at a quicker rate. The players had a greater understanding of how to move the ball faster up the court. There’s more dribbling today. It’s more a perimeter, spread-out offense.”

The consensus, of course, is that a shot clock could help remedy the pace of the game. It’s a debate that continues to rage across the state. The financial piece remains a major stumbling block for schools. Whether its implementation would translate into getting some more 2,000-point scorers to surface is anyone’s guess. It couldn’t hurt.

In recent years there have been some close calls. Luke Merrill (story on him next week) scored 1,975 points for Pittsburg, the state’s northernmost school, where he played five years from 2003 to 2008. Keith Brown, a 2016 Pelham HS grad, filled it up to the tune of 1,978 points, leading the Pythons to back-to-back D-III titles. Essentially, one more game would likely have gotten either player over that milestone hump. Almost.

Getting there, however, remains elusive.