By Mike Whaley

Gary Jenness may be in his “golden years” but that doesn’t mean he’s slowing down. Not one little bit. After successfully coaching high school girls basketball at Groveton and White Mountain Regional from 1978 to 2016, Jenness, now in his mid 70s, has remained active at White Mountains at different times as an athletic director at the high school and currently at the middle school. He is also a state supervisor for basketball officials, while still officiating that sport and soccer. He took a recent fall that has put his basketball officiating on hold for the moment. In the summer, Jenness works at Santa’s Village in Jefferson.

“When I retired a couple of good friends of mine said you need to stay busy. Find something you like,” Jenness said. “As I told my wife (Marjorie) because she asks me why I come to school every day – ‘I like being busy. I’m not going to sit around. I’m going to stay busy. I’m going to do stuff I like, and when I don’t like it anymore, I’ll get done doing it.’ And so far that hasn’t happened.”

Jenness was very busy indeed during his coaching stints at Groveton and White Mountains. He has won more games (641) than any other high school girls basketball coach in New Hampshire and is second overall to the late Dan Parr (704), with his teams winning 12 state titles (11 at Groveton and one at White Mountains). He has also received many coaching honors and has been inducted into five halls of fame.

Coaching was always on his radar. A native of St. Johnsbury, Vermont, Jenness was inspired to coach by his dad — Harold “Pete” Jenness – an excellent youth coach, and his dad’s friends who coached, as well as his high school coach, Lenny Drew, and JV coach Scott Ingram.

As a senior at St. Johnsbury Academy, Jenness was a captain of the basketball team along with Paul Simpson. The two used to sit right behind the two coaches. “Not because we were trying to (brown nose); they had a wealth of knowledge with everything they did. They just knew so much about life and sports.” At the end of practice, Jenness and Simpson would sometimes play games of 2 on 2 against their coaches.

“When I graduated from high school I decided I wanted to be a coach,” Jenness said. “(Drew) was a history teacher, so I figured I’d be a history teacher.”

He enrolled up the road at Lyndon State College (now VTSU-Lyndon), but quickly found out he wasn’t going to be a history teacher. “My first assignment, I think it was called European Civilization, was to read 300 pages for the next class. I said that’s not for me. I’m not going to read 300 pages.”

Jenness bounced around after that. He got married to his first wife. He fell off a roof working for Rodd Roofing, so he was laid up and couldn’t go to school. He joined the National Guard and missed a year of school there.

He also remembers his first coaching position. It was 1967-68 and he coached a traveling middle school boys team. Jenness was working for Rodd at the time. “Mr. Rodd’s son was an eighth-grader,” he recalled. Rodd had two old Ford station wagons with wood paneling on the sides. “I’d drive one and he’d drive the other. We played 42 games that year and went to five tournaments. He would take us everywhere, and then take the kids out to eat afterwards.”

Jenness remembers working for a construction company in January of 1969. “I was cutting brush and stuff with snow up to my rear end,” he said. “I went home and told my wife at the time, ‘I’m going back to school to become a teacher and coach.’ Manual labor wasn’t for me. It had no future.”

Lyndon, by then, had a physical education major, so he went back to earn his degree and graduated in 1973, eight years after he graduated from high school.

His first job out of Lyndon was as a PE teacher and coach at Gilman (Vermont) Elementary School. It was quite a learning experience. “It’s a mill town. The kids were tough,” Jenness said. “They really didn’t think there was any need for school. I had some stuff that happened that if it happened now I’d be fired; actual physical fights with an eighth-grader. Stuff like that.”

Jenness was seriously thinking of getting out of teaching when a job opened up across the border in Groveton. It turns out he had an in. The superintendent of schools for Groveton was godfather to Lenny Drew’s first child. “When I mentioned I was from St. Johnsbury and played for Lenny, that helped,” Jenness said.

He was hired as a high school PE teacher and coached the junior boys basketball team. At the time the Groveton boys teams were very good and there was a feeling that coach Fred Bailey was leaving and they wanted someone to replace him when he left.

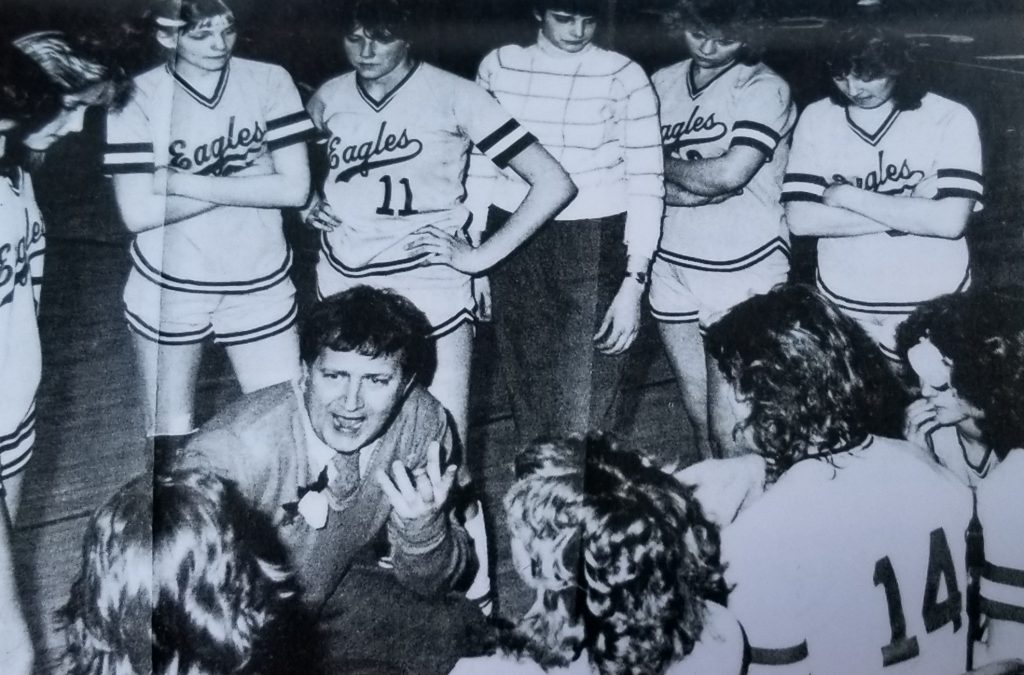

The varsity girls’ position opened up in 1978. “I took it,” Jenness said. “After a year of doing girls basketball, I said I’d never coach boys again.” He coached the Eagles until 2006.

“The girls were just eager to learn,” Jenness said. “They worked hard and didn’t think they knew everything.”

Not that it was all peaches and cream. “I had a hard time and they had a hard time with me because I was a bit of a hard ass,” Jenness said. “After a few days of crying and everything, they figured out I really wasn’t that bad of a guy. That’s the way I was going to coach.”

Jenness had a good run at Groveton, but it took a while to get it to where he wanted it. One thing he did was encourage the girls to play during the summer, which became a collective mindset as the program improved and evolved. “We started getting halfway decent,” he said. “People started to have to worry about us.”

By the mid 1980s the Eagles were becoming a factor in Class S (now Division IV). They stayed there for the next 20 years under Jenness, and continue to excel to this day. The span from 1986-87 to 2006, Groveton went to 14 championship games and won 11 titles.

The Eagles at two separate stretches won four and then five consecutive state titles. “Guys at other schools kept telling me that after this year, next year we’re going to kick your ass,” he said with a laugh. “We were very seldom rebuilding. The one thing I found was that Groveton was a sports town – especially a basketball town. All the kids would play down at the elementary school basketball courts. I always said ‘success breeds success.’ Those little girls who were down on the playground playing were pretending they were some of the players who were on the varsity. They just couldn’t wait to get up there and play for Groveton High School. I’m not sure they wanted to play for me all the time, but they definitely wanted to play for Groveton.”

Jenness tells the story about in 2000 when the boys and girls programs were really good (both in the midst of winning multiple titles in a row). Bill Bradley, the United States Senator from New Jersey and former college and NBA star, was running for president. His campaign had him come to Groveton. He met the two high school teams and shot some baskets with them. Jenness got a signed copy of one of Bradley’s books.

Groveton was very good for its division, but they also did well against bigger schools. One year when they won the Class S title, Littleton won in Class M and the Eagles split with them. Jenness recalls playing in a preseason jamboree in Goffstown with Class L and I schools and holding their own. “There’s a couple of years we wouldn’t have won the big classes, but we would have competed,” he said.

Another advantage in Groveton was that Jenness picked the coaches from elementary school on up. Tim Haskins was his long-time JV coach and now coaches the varsity. “I didn’t have to teach the basics to the kids,” Jenness said. “We could work on Xs and Os, which I like.”

It was a challenge when he made the move to White Mountains or “The Regional”, originally attracted to the position because there was the chance to coach his granddaughters. He found the girls to be athletic, but not skilled like his Groveton girls. One thing he did early on was overlap varsity and JV practice for 15 to 30 minutes to work on basic skills – two-handed chest pass, bounce pass, jump stop, pivot. “Just little things that when I played against The Regional I never really paid attention to the fact that their skill levels weren’t very good,” Jenness said. “They were athletic. They just made too many little mistakes in terms of their skills.”

Another challenge was that White Mountains has a strong softball program, and that made Jenness adapt as far as summer basketball. Girls were playing softball games all summer, and were less likely to show up in a hot gym to practice, so he compromised, scheduling more games.

The Spartans went on a good run from 2010 to 2013, appearing in the semis and two championship games. They won the 2012 D-III state title. On the eve of the 2011 semis vs. Campbell, his granddaughter, Emily, got mononucleosis and couldn’t play. She was a key cog in the middle of the 1-3-1 zone defense. Jenness had to put another player there. “It didn’t turn out very well,” he recalled. “We missed our first four layups and they made their first five shots.”

Jenness came back for another year and White Mountains won the championship. In 2013 they lost in the final to Bow, a game where Jenness said “we set girls basketball back 30 years. We scored eight points in the first six minutes.” But did not score much after that in an ugly 29-17 loss.

There were several girls who had been around the program since they were in eighth grade. They asked him to stay until they graduated. “Being a softy, I stayed until they graduated in 2016,” Jenness said. “I knew when they were done, I was done. … I felt I owed those girls for being part of the program.”

When he stepped down, it ended a 38-year run as a varsity high school coach and a 40-plus year career overall. He also coached boys soccer for five years at Groveton, and served a stint as the school’s athletic director.

Although he isn’t coaching, he keeps on top of the sports scene as an official, a supervisor and an AD. “It gets more challenging,” Jenness said. “It’s a little different from what I was used to in Groveton and the first few years at White Mountains. There’s too much to make everybody feel good, whether they do anything. When they don’t feel good, it’s the coach’s fault. It’s the athletic program’s fault. Everybody gets a trophy. The thing that gets me after a game, I’ll hear parents say ‘you guys played so well. No, they didn’t play very well. Well we got beat by 35 points, so probably they didn’t play that well. That’s society now. You can’t hurt anybody’s feelings.”

Jenness said there are some very good coaches in the North Country with the same philosophy, noting Buddy Trask (Colebrook), Mark Collins (Groveton) and Trevor Howard (Littleton) among others. “One of the reasons these programs were always at the top of Class S and then Division IV was because the coaches held the players accountable and you had to work to play,” he said. “You had to work to get minutes. Now I think sometimes coaches, if a parent complains, the easiest way to stop the complaining is to let them play for a few minutes and that the parents are happy whether they deserve the minutes or not.”

Jenness tells his young coaches to be consistent and fair in what they do. “Then I can back you 100 percent,” he said. “But if you let somebody do something and somebody else can’t do it, it’s pretty hard for me to back you because you’re not consistent.”

In both Gilman and Groveton, Jenness recalls running into kids who couldn’t understand why they had to take some courses. “Like their fathers and grandfathers before them as soon as they graduated, they were going to the (paper) mill,” he said. Then the mills started wanting people that were more qualified to do certain things. “Kids started catching on. ‘We better go to school.’”

Jenness said mill towns can be funny. He recalls in 1995 Groveton was looking to change its athletic policy. A lot of coaches were doing their own thing as far as kids missing practice and missing games. Jenness said the night they made the presentation to the school board, the English department presented their curriculum to the board, and it took all of 20 minutes. It took the rest of that meeting and another meeting to get through the athletic policy.

“All the parents were there,” Jenness said. “If it was something that didn’t affect them, they were all for it. But if it was something about going on vacation and (kids) going to have to sit games, then they were up in arms.”

There were times back in the day, noted Jenness, when there was money won and lost at the mills on high school games between Colebrook and Stratford (closed in 2012), Colebrook and Groveton, and Stratford and Groveton. “Those millworkers would bet pretty heavily on those games,” he said.

Back in the 1990s, Jenness can remember when Colebrook and Groveton were playing, if the game started at 5:30 p.m., the doors opened at 4:30 because the place would be packed. He can also recall going to Stratford for a boy/girl doubleheader. “I was always pissed because the girls played first,” he said. “When we came out after we played, there was no place to sit.”

At one point, Jenness worked with Trask in Colebrook to do home/away games on Friday and Saturday nights. Each year they would switch off who was the home team on those nights. “We’d fill the stage with people because that’s how many people came to watch those games,” he said. “The teams were very good. The towns were very athletic-minded. Now very seldom do you see a gym full. Groveton plays Littleton, the gym will be full, but not like it was in the old days.”

Jenness can remember doing a lot of scouting, as did Trask and Collins. With the advent of streaming services like Northeast Sports Network (NSN), coaches can watch games online and spend less time on the road scouting.

Jenness remembers in 1986-87, he and Haskins, his JV coach, saw every Class S girls team. “We’d have early practice, I’d say to him ‘want to go to Nute tonight?’” Jenness said. “He wasn’t married. It was between marriages for me. Those days we’d just take off and we’d get out somewhere. They’d say ‘what the hell are you doing here?’ I’m never going to lose a game because I don’t know what somebody is going to do.”

That started, Jenness said, when he called a coach at Lin-Wood for a scouting report. “Her words were: ‘they’re nice kids. They were so nice.’ That’s nice, but that’s not going to help me win a basketball game.”

Jenness said Trask scouted right up until he retired two years ago. “Mark Collins still scouts some. You never see coaches or assistant coaches from other schools. Very seldom do you see them watching a game and scouting.”

As a basketball supervisor, Jenness is concerned with the decline of young officials entering the profession. The numbers he has for N.H. is that 67 percent of officials are over age 60. Of that remaining 33 percent, 75 percent of that number is over age 55. “There are so few young officials that stay at it long enough to get good enough to get tournament games,” he said. And if they do stay, they end up getting recruited to do college games where the money is better. “That’s great for them, but it just waters down what we have to offer.”

Jenness is also on the New Hampshire Interscholastic Athletic Association (NHIAA) Awards Committee with Executive Director Jeff Collins and some other veteran ex-coaches and administrators like Bill Dod, Bob Nelson and Peter Cofran. “We’ll get talking about something that happened back in the 1970s and 1980s, and Jeff will sit there and say ‘did that really happen?’” Jenness said. “Peter’s the chairperson and, of course, he ran all those tournaments at Plymouth for all those years. It’s funny we’ll sit there and sometimes we’ll get off on a tangent talking about whether somebody should be in the hall of fame. We’ll go away from that person and something related to that person or somebody that person knew, and (Jeff) won’t stop us and say we need to get back on track here. Most everybody on the awards committee has 40 years of service to the athletes in New Hampshire and the NHIAA.”

An always-in-motion Gary Jenness stays the course in a rapidly changing athletic environment. The landscape is light years removed from what he grew up with in the 1960s and became accustomed to as a coach in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, and even into the new millennium. No matter, Jenness adapts here and there and largely remains who he’s always been, an older and surely wiser version of his fair and consistent self.