By Mike Whaley

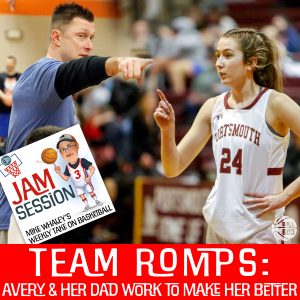

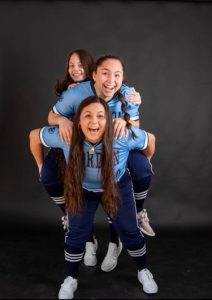

Unlike most athletes, Avery Romps has a built-in trainer and coach in her dad, Mike. Pretty sweet deal if you can get it.

Unlike most athletes, Avery Romps has a built-in trainer and coach in her dad, Mike. Pretty sweet deal if you can get it.

Avery attends Portsmouth High School where the 5-foot-11 junior stars on the Clipper girls basketball team, which is 6-1 in Division I.

While Avery is helping Portsmouth to experience another strong season in D-I and work her way to college at the NCAA Division I or II level, her dad is helping her to be the best that she can be.

Mike is a Grade 2/kindergarten teacher in Dover, a life coach and personal trainer, and a former varsity boys basketball coach at Dover High School.

He played basketball in high school at Manchester Central and then at Plymouth State University. He got into coaching after college as an assistant at now defunct Daniel Webster College, followed by stops at Keene State, Central Missouri State (where he met his wife, Jackie) and the University New Hampshire. Mike was the head coach for one year at Tilton School, before he took the Dover job. Basketball has been a big part of his life, as it has for Avery.

When Mike was the head coach at Dover High for 15 years (2001 to 2016), his two daughters spent many hours in Dover’s old Ollie Adams Gymnasium.

He recalls, at the time, having three job offers at Dover, Portsmouth and Berwick Academy. “I felt it was important to live, teach and coach in the same community,” he said. “The only place we could afford to live was Dover.”

Mike remembers a lot happening in 2001. It was his first year teaching and coaching in Dover, Jackie got pregnant with their older daughter, Samantha, and they got married.

Mike remembers a lot happening in 2001. It was his first year teaching and coaching in Dover, Jackie got pregnant with their older daughter, Samantha, and they got married.

Samantha was born in 2002. “From then on, the girls were in the gym,” said Mike, who has taught in Dover for 23 years, the last 21 years at Garrison School. “People were babysitting them left and right. They were at all the games.”

Avery was born in 2006. She smiles about her early basketball memories with her dad. “We would always be in the gym running around,” she said. “I don’t remember the games, but it was fun being on the sidelines all the time. I was so young. It was a bunch of these tall guys. It was really nerve-wracking. It definitely made me interested in basketball a lot more; the game in general. How to play.”

Mike recalls Avery in her bouncy seat with her basketball with her name on it. “I can remember her running up and down the bleachers,” he said. “Listening in timeouts; getting snacks and candy during the games. From the jump, I don’t think there was a day when there wasn’t something like basketball in our lives.”

With Samantha, Romps said he was a little more “cautious and cerebral” because she was the eldest, the first child. He stayed at arm’s length as far as coaching her. Samantha went through the Dover school system, playing basketball as well. She graduated from Dover HS in 2019.

Mike felt Avery had more of an edge on her, and he felt she really liked the sport. There was also a very good group of similar aged Dover athletes – Tory Vitko, Payton Denning, Julia Rowley, Lanie Mourgenos.

By the time Avery was in second grade, she was not only playing Little Shots with the Dover Recreation Department, but also traveling to tournaments. Mike coached those teams, which did very well. “I would like to think they’re all reaping the rewards now,” he said.

Avery recalls the four-team rec league being fun. The travel ball allowed the girls to play against better competition. “That helped us improve at an early age,” she said.

Avery recalls the four-team rec league being fun. The travel ball allowed the girls to play against better competition. “That helped us improve at an early age,” she said.

If you know Mike Romps, he is an intense person. When he coaches, he has a lot of fire and energy. Avery is lower key. Early on she was not as receptive to his criticism as she is now.

“When I was younger I was a little more sensitive,” Avery said. “He would critique me too much and I just couldn’t (take it).”

But then Avery got to the point where she could see that her dad’s suggestions were helpful. “Now I take them and try to improve my game and it obviously works,” she said.

Although he’s not so sure now, at the time he coached Avery and the girls hard. “We were very clear with the parents,” he said. “The Sue Vitkos of the world and people like her, they were just as into it as I was.”

Mike always kept in mind that they were young kids and he couldn’t treat him like high school players. But he felt strongly about accountability, defense and rebounding. “There was a lot of the time I would pull someone out of the game, “ he said. “I think that’s the hard part of being a parent-coach, that your first inclination is to be hardest on your kid because you know all the parents are watching and keeping track.”

Fortunately, there were few issues. Mike had this group of girls from Grade 2 until Grade 8, and they did very well. “It was just a situation where they were used to being coached like that,” he said. “Everyone was kind on the same page, which made it a special time for all of us.”

Avery laughs at some of those memories, which weren’t always rosy. “At times, it was not fun,” she said. “I improved a lot mentally. If a coach is going to yell at me, I’m that much mentally stronger now.”

Avery laughs at some of those memories, which weren’t always rosy. “At times, it was not fun,” she said. “I improved a lot mentally. If a coach is going to yell at me, I’m that much mentally stronger now.”

The silver lining was that the team did very well and Avery got better as a player. “Two years we were undefeated,” she said. “It just made the game so much more fun to play, especially with these girls because we were all good friends.”

Things changed just before Avery went to high school. The family decided to move to Greenland. Several factors played a role in that move. Mike’s parents were now living with them. He was also looking to enhance his business as a life coach and personal trainer. The Greenland property provided space for a full basketball court and land to run camps.

The move meant a new start at a new school for Avery. Mike understood that. He just wanted to make sure she was surrounded by good people, like she had been in Dover. It also meant he needed to step away from his daughter as a coach.

As it turned out, Mike had coached some of the Portsmouth girls in a summer league in Danvers, Mass. “We were lucky to know most of the parents,” he said. “We had conversations and asked if they were open (to Avery coming to Portsmouth). They were welcoming and warm from the jump.”

It still wasn’t easy. Due to the pandemic, Avery did not attend classes in person until January of 2021. Basketball, which started in January due to the pandemic, made things easier.

“I remember going to the first couple of open gyms and I was so nervous,” she said. “I knew these girls from playing against them when I was younger. We always played against each other and it was competitive, but now we’re going to be on the same team. It was definitely different. But after a couple of open gyms, I got super close with a lot of them. It became so much more fun.”

Plus the team had success. Avery was one of four freshmen who played significant minutes along with Maddie MacCannell, Margaret Montplaisir and Mackenzie Lombardi. The Clippers made a run to the D-I semis, which included an upset of a veteran Exeter club in the quarterfinals.

Last year as sophomores, they had another strong year, again making it as far as the semis. Avery was named to the D-I All-State Second team. “With that, there’s a target on their back this year,” Mike said.

Mike also appreciates how the Portsmouth program is handled. “Coach (Tim) Hopley runs the program the right way,” Mike said. “I respect the way he runs it. He is a defensive-minded coach. It’s made the transition much easier for everybody.”

For Hopley, the Romps situation had always been a good one. “There has never been a time when (Mike) overstepped his boundaries,” Hopley said. “He works with a lot of our players in the offseason. … He’s done a lot to certainly help Avery’s game, but also to help all of the players in our program or at least give them the opportunity to help them improve.

“It’s a situation for me where I know they’re being taught great fundamental skills when they’re with him,” Hopley said. “He’s respectful of what we try to do in our program. I never get the sense with Avery that she’s in conflict. It’s a great situation. There’s no other way to put it.”

Now that she’s a junior, Avery is starting to consider colleges. She has one offer from Saint Anselm College, a D-II school in Manchester. “I’m still waiting,” she said.

In the meantime, she plans to work on her game and do her best to help the Clippers advance as far as they can in the D-I tournament.

“The big thing I have worked on this year is my aggression,” Avery said. “Last year, I was a shooter and just attacked when I was open. This year I’m really trying to initiate the contact. I have way more intensity. I’ve improved in that way.”

Mike said that improvement is clear in the numbers. Avery’s grandad keeps her statistics. Last year she took 50 free throws. Through five games this year she has already taken 39. “That’s a barometer that you are attacking the rim,” Mike said.

Similar to that point, Hopley weighs in on Avery’s need to be more physical. “She is starting to play the game in a more physical manner, which is what is required not only to play at a high level in high school but to play at the college level,” he said. “I think that’s one of those things she’s continuing to work on. She’s made huge strides in that part of her game.”

Hopley pointed to a game last week with Pinkerton (71-62 win) in which Avery took over in the second half. “She was willing to be physical, attacking the paint,” he said. “I think she drew two ‘and-ones’. Those are things she might not have done her first two years in our program.”

There have been some interesting Romps car rides where the conversation comes around to being more aggressive. “What we’re saying is there have been times throughout her career that she wasn’t,” Mike said. “I come back to her: ‘You’re putting in the time. Go out there and show people what you can do.’ There were times when it got intense and I was told by my wife to shut up, to leave it alone.”

Avery also feels she has improved defensively. “I have this non-stop motor on the court,” she said. “I’m always playing intensely, supporting my teammates. I’m not getting down on myself when I miss shots.”

Mike says the schools that have been looking at Avery have been clear about what they want to see. In their training sessions together, Avery has been very receptive to what Mike puts out there. She also uses the weight room in the family basement to improve her strength. “She’s learned that there are certain things outside of practice she has to do,’ Mike said. “Whether that’s getting up shots, lifting weights or going for runs.”

Portsmouth, in Mike’s opinion, is letting Avery create more, to be a facilitator on the court. “There are a lot of pieces to Avery’s game that the average Joe might not see,” Mike said. “But whether it’s covering the best player or bringing the ball up the court or making that extra pass or rebounding, I’m just proud of the basketball player that she is. She is definitely a coach’s kid in that regard.”

Mike believes the only thing holding her back is she needs to be a little more selfish. As an example, Mike points out that Avery is big on making that extra pass. It’s something she’s always done. “Sometimes, hey, you’re the one who just took 500 shots, you shoot it,” he said. “There’s that balance of selfishness and team play and being a coach. I’ve always taught her to make the right play. Now I’m turning around and telling her to shoot that shot. It can be confusing at times. We’re still working on it.”

Avery does see the wisdom in what her dad is saying. “Especially since I put in so much time,” she said. “I wasn’t showing anyone that. I was just being an average player. Just doing what was open. Now it’s clicked in the past couple months. I have all this skill. I can finally show people since I put all this work in.”

Mike regrets not putting enough time into his own game. That makes him more than ever want to help his daughter maximize her potential. “I’m going to do everything I can as long as Avery is open to it,” he said. “To make her as good a player as she can be.”

He pauses, adding: “When push comes to shove, I’m just the person rebounding and making suggestions. She’s the one that has to do the work.”

Have a story idea for Jam Session – email whaleym25@gmail.com.

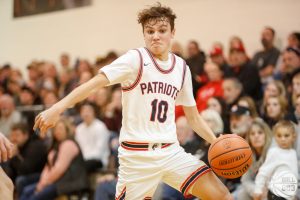

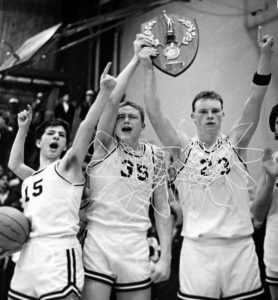

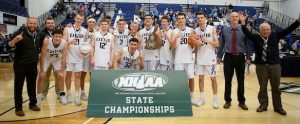

Mitchell Roy has a plan. It is a four-year project to elevate the Profile High School boys basketball team from the Division IV cellar to the championship podium – something that has happened just once in school history (2004).

Mitchell Roy has a plan. It is a four-year project to elevate the Profile High School boys basketball team from the Division IV cellar to the championship podium – something that has happened just once in school history (2004).

Roy got to be part of coach Kevin Bettencourt’s program at Endicott as a manager and then student assistant. The Gulls did well, advancing to three Commonwealth Coast Conference championship games and a NCAA Division III Sweet 16. There he was able to work with some tremendous New Hampshire players like Portsmouth’s Kamahl Walker, Pelham’s Keith Brown and Dover’s Ty Vitko.

Roy got to be part of coach Kevin Bettencourt’s program at Endicott as a manager and then student assistant. The Gulls did well, advancing to three Commonwealth Coast Conference championship games and a NCAA Division III Sweet 16. There he was able to work with some tremendous New Hampshire players like Portsmouth’s Kamahl Walker, Pelham’s Keith Brown and Dover’s Ty Vitko.

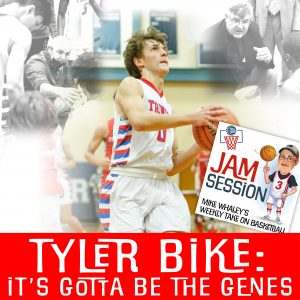

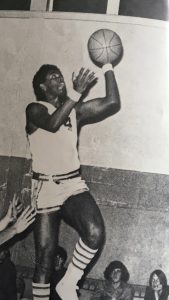

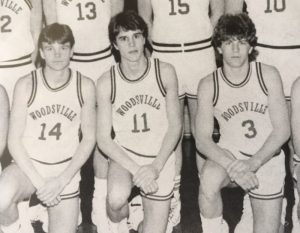

If you’ve seen Tyler Bike play basketball and you’re unaware of his family’s impressive gene pool, you’d still agree he’s pretty darn good. But if you knew about the gene pool, you might just say to yourself, “Well, that certainly explains that.” Which, of course, it does, except genes alone don’t get the job done. Tyler Bike knows that.

If you’ve seen Tyler Bike play basketball and you’re unaware of his family’s impressive gene pool, you’d still agree he’s pretty darn good. But if you knew about the gene pool, you might just say to yourself, “Well, that certainly explains that.” Which, of course, it does, except genes alone don’t get the job done. Tyler Bike knows that.

Growing up, Keith certainly soaked in being the son of a college coach, starting as a ball boy for Dave’s team. “I was the slowest kid every time I stepped on the court,” Keith said. “I had a good knowledge of the game. A lot of that had to do with me watching my dad’s teams and players growing up. Just being the kid on the bench.”

Growing up, Keith certainly soaked in being the son of a college coach, starting as a ball boy for Dave’s team. “I was the slowest kid every time I stepped on the court,” Keith said. “I had a good knowledge of the game. A lot of that had to do with me watching my dad’s teams and players growing up. Just being the kid on the bench.”

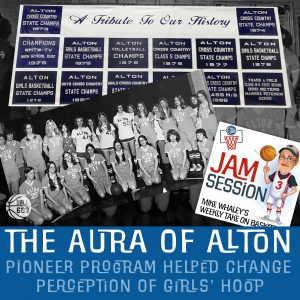

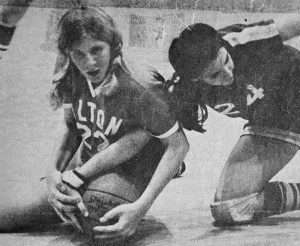

(Note: Little Alton High School was the state’s first small-school girls basketball power in the 1970s. They won three state championships in four years, amassing at one stretch a 64-game winning streak. It seems fitting to recall those Alton pioneers on the 50th anniversary of Title IX – the 1972 federal anti-discrimination, civil rights law, which helped to close the athletic gender gap and led to a considerable increase in the number of females participating in organized sports in high schools and universities. Quotes from the main Alton players are from a 1988 story that appeared in the old Rochester (N.H.) Courier. None of the women responded to recent requests for comment for this story.)

(Note: Little Alton High School was the state’s first small-school girls basketball power in the 1970s. They won three state championships in four years, amassing at one stretch a 64-game winning streak. It seems fitting to recall those Alton pioneers on the 50th anniversary of Title IX – the 1972 federal anti-discrimination, civil rights law, which helped to close the athletic gender gap and led to a considerable increase in the number of females participating in organized sports in high schools and universities. Quotes from the main Alton players are from a 1988 story that appeared in the old Rochester (N.H.) Courier. None of the women responded to recent requests for comment for this story.)

By Mike Whaley

By Mike Whaley

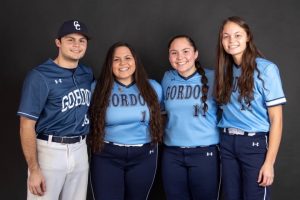

Ami and Isabella, however, were constant teammates at Brady in softball and basketball. They were key contributors to the school’s first state girls’ basketball championship team in 2021. The Giants beat Kennett in the Division II final, 52-50, on Isabella’s steal and layup in the waning seconds.

Ami and Isabella, however, were constant teammates at Brady in softball and basketball. They were key contributors to the school’s first state girls’ basketball championship team in 2021. The Giants beat Kennett in the Division II final, 52-50, on Isabella’s steal and layup in the waning seconds.

Shaw is glad he has Ami and Isabella on his team. Ami is the point guard, while Isabella is a shooting or off guard.

Shaw is glad he has Ami and Isabella on his team. Ami is the point guard, while Isabella is a shooting or off guard.

By Mike Whaley

By Mike Whaley

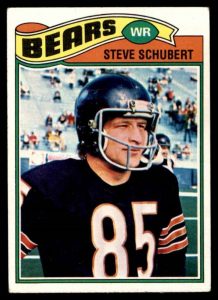

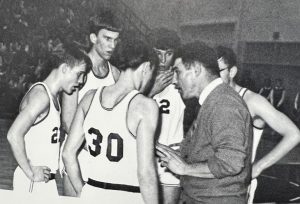

Jeff accepted a scholarship to Boston University, but never played under Pitino. On the eve of the season, the coach took a position as an assistant with the New York Knicks – a season that Jeff ended up spending on the BU bench.

Jeff accepted a scholarship to Boston University, but never played under Pitino. On the eve of the season, the coach took a position as an assistant with the New York Knicks – a season that Jeff ended up spending on the BU bench. It was a great experience. It’s where he met his wife, Janel.

It was a great experience. It’s where he met his wife, Janel. From Ball he learned how to run a program, including how to increase your participation numbers. “I developed that over the years,” Holmes said. “We’ve got good numbers for freshman and JV. We have a lot of competition for spots.”

From Ball he learned how to run a program, including how to increase your participation numbers. “I developed that over the years,” Holmes said. “We’ve got good numbers for freshman and JV. We have a lot of competition for spots.” Although there was success the two years after that, there was also frustration because of the pandemic.

Although there was success the two years after that, there was also frustration because of the pandemic.