By Mike Whaley

When Woodsville won the 2021 Division IV high state school boys basketball championship, it removed the proverbial monkey off its back. The Engineers celebrated their first hoop title in 44 years, dating back to the 1970s when legendary coach John Bagonzi prowled the sidelines.

When Woodsville won the 2021 Division IV high state school boys basketball championship, it removed the proverbial monkey off its back. The Engineers celebrated their first hoop title in 44 years, dating back to the 1970s when legendary coach John Bagonzi prowled the sidelines.

It’s been a long journey back to the top for the little New Hampshire border school. For the uninitiated, the village of Woodsville (1,400 pop.) is located 40 minutes north of Hanover, N.H. It partially sits on the banks of the Connecticut River, the state’s natural border with Vermont, just across the Veterans Memorial Bridge from its neighbors in Wells River, Vt.

With four returning starters, Woodsville is looking to defend that title this winter. The top-seeded Engineers carry a perfect 18-0 record into the D-IV state tournament as the lone unbeaten boys’ team in the state. They will host No. 16 Hinsdale Monday night in the first round of the tournament, which culminates March 11 with the championship game at Keene State College.

With the exception of wins over their Vermont neighbor at Blue Mountain Union by 8 and 19 points, the Engineers have beaten every single one of their N.H. opponents by at least 21 points. They have outscored the opposition by an average of 69 to 33 in 18 games. Only twice in those 18 games has an opponent managed to score more than 50 points, and only seven times 40 or more.

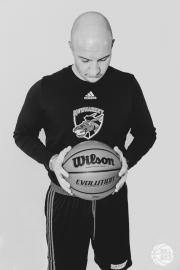

Under Woodsville alum Jamie Walker’s guidance, the Engineers have been a consistent playoff participant in D-IV since the early part of the century. However, until last winter, Woodsville had been unable to collect the big prize, taking a backseat behind other North Country programs like Colebrook, Groveton, Lisbon and Littleton.

ENGINEERS FINALLY BREAK THROUGH

Walker knew he had something coming into last season, but not necessarily a championship caliber squad. “I thought we would be competitive,” Walker said. “We had done all right the previous year. By no means did I think we’d win it all. But I thought we had a chance to be really good.”

With a team made up of freshmen, sophomores and juniors, the Engineers did just fine in 2020. But things ended badly in the quarterfinals at Newmarket, a 63-26 pasting.

That loss left a bad taste in everyone’s mouth.

“I was really frustrated after my sophomore year,” said senior forward Elijah Flocke. “I felt like we had a good team with Cam Tenney-Burt coming in (a transfer from Lisbon). I felt like we could have gone further. Newmarket was a really good team. It was a wakeup call that there were bigger fish in the water. Coming into my junior year, I wanted to be that big fish.”

“We were unhappy with the year before, so we just wanted to come out and prove a point that we were one of the better teams,” said junior forward Cam Davidson.

Walker shakes his head about the Newmarket game. “I never told the kids this, but it was just men playing against boys,” he said. “We were sophomores and juniors playing against really rugged juniors and seniors. We couldn’t get a rebound, and they couldn’t shove us out of the way fast enough to grab another one.”

Although Walker’s son Brendan transferred to Kimball Union Academy in Meriden, N.H, to focus on baseball (he’s been recruited as a pitcher by NCAA Division I Stetson University in Deland, Florida), Woodsville returned most of its lineup intact.

Four of the primary players were talented underclassmen (three juniors and a sophomore). The one senior was indispensable point guard Corey Bemis. “At the end of games he was the one we put the ball in his hands,” Walker said. “He was the one getting us to that set or situation that the basket was made. He was the kind of kid every championship team needs. He does all the stuff that’s not noticed or isn’t in the scorebook. You know, without him on the floor, you’re in a lot of trouble.”

The Engineers opened with an 84-48 win over Colebrook, the first of three straight wins, before they hit a road bump. They lost three of their next four, but two were against bigger schools (D-III White Mountains and D-II Kennett). There was a feeling that even though they lost to Kennett by six on Feb. 10, 2021, that was a turning point.

“After we played Kennett, I felt like we could contend with anybody in Division IV,” Flocke said.

Woodsville has not lost a game since. They won their final four of the regular season, collected five wins in the tournament and 18 this year to run their current streak to 27 – and counting. It’s the longest active boys’ streak in the state.

In the 2021 tournament, Woodsville (13-3) rolled through the first two rounds over Lin-Wood, 54-34, and Lisbon, 49-18. Flocke’s 22 points paced the Lin-Wood victory, while Mike Maccini and Tenney-Burt split 24 points vs. Lisbon.

Walker points to the 48-42 quarterfinal win at Concord Christian Academy as a critical moment in that run. “When you win a championship there’s one game that could have gone the other way,” Walker said. “That was definitely the game.”

Woodsville played nervously at the start. “We had never seen Concord Christian,” Walker said. “We knew they were big, but we didn’t know how big. They were 6-6, 6-4, 6-3. They were just big people.”

Indeed, the Engineers found themselves down 22-8 in the first quarter. Davidson was sitting next to Walker in foul trouble, and to make matters worse, Tenney-Burt rolled his ankle and had to leave the game for a short period.

It wasn’t looking good.

“I looked at my assistant,” Walker recalled. “‘I’ve got to put Davidson back in. It doesn’t matter if we sit him until halftime if we’re down 35-10. That’s not really going to help us.’”

The gamble paid off. Davidson sparked a 19-4 run that put Woodsville up 27-26 at the break. They widened the lead to 39-30 after three. In the fourth, CCA cut the lead to four, but Maccini hit a big 3-pointer and drained some clutch free throws to help secure the six-point win. Maccini, Davidson and Tenney-Burt each had 12 points.

Next up in the semis at Plymouth Regional High School was Groveton, the most successful team in the history of Division IV basketball with 10 state titles. Normally, the Engineers would have played Groveton during the regular season, but because of covid, they did not play some of the North Country schools, including the Eagles.

“Groveton and (coach) Mark Collins, nobody likes playing him in a semifinal or championship game,” Walker said. “He usually finds a way to win. It was good to get over that hump. It was good that we hadn’t played them. They didn’t know us.”

Of course, Woodsville had its predictable slow start, as had been the case in the previous three playoff games. They only scored three points to trail 8-3 after eight minutes.

“We didn’t score in the first four or five minutes of the game,” recalled Walker. “Kids were dribbling off their feet. One ball was eight feet over someone else’s head. We were just nervous.”

Walker called timeout, telling the Engineers to relax. “It’s just a basketball game,” he said. “Maybe a little more at stake here. Just settle down.”

Groveton presses all the time, that’s what they do. One thing Walker noticed was that Woodsville was breaking the press, but stopped at halfcourt and let all five of Groveton guys get back on defense, instead of exploiting a 2-on-1 or 3-on-2 advantage.

“In the timeout I said ‘you’re getting by the first four guys,’” said Walker, who played his starting five the whole game without subs. “‘Why are we stopping and letting them get back? Attack the one or two guys that are back’ We started doing that and we started scoring.”

Led by the two Cams (20 points each), they responded in the second quarter with a big surge to go ahead 25-16 at the half, and were able to maintain a cushion the rest of the way en route to a 56-50 victory.

“That game was just a big hump for us,” Davidson said. “So getting over that was a realization factor that we could make some history.”

Standing in the way of that first title since 1977 was Portsmouth Christian Academy, a southern team from the Dover area. PCA had never won a boys basketball championship, so it was chasing some history of its own.

Unlike the previous four playoff games, the Engineers actually started fast, going up 13-6 after the first quarter. But Flocke and Davidson each picked up their second foul and had to sit the entire second quarter.

“I didn’t know how long I was going to sit them,” Walker said. “The score was 19-17 (PCA) at the half. There was no sense of urgency of them pulling away from us to put those guys back in to try and keep it close. I didn’t have to gamble on their third foul being picked up.”

The two were reinserted in the lineup to start the second half. Woodsville immediately went on a run, and their defense locked down PCA. They regained the lead to go ahead 29-21 after three quarters, holding PCA to two points.

That carried over to the fourth quarter where their lead eventually expanded to 25 points before they finished off the 52-30 championship win. Flocke and Tenney-Burt had 15 points each, while Davidson added 14.

Woodsville was in a state of championship euphoria.

“It was pretty crazy,” said Mike Maccini, a senior point guard. “The bus ride back from Plymouth to Woodsville wasn’t very long, but it’s a long, flat stretch. There were definitely fireworks. There was a pretty long parade. There was a really special feeling back in town.”

Walker laughs as he recalls some of those championship moments. “It’s kind of funny, my first assistant coach before Rob Maccini was Bill Grimes,” he said. “Bill Grimes was a player on the last (championship) team in 1977.”

Grimes coached with Walker through the 2019-20 season, but moved to Florida before last season or he would have been an assistant on the championship team. “He would have been on both ends,” Walker said. “One as a player. One as an assistant coach.”

Grimes followed the Engineers in Fort Myers, Fla. He works at a golf course and actually had the semifinal and championship game streaming on the course’s pub TV. “He coached everybody on that team,” Walker said. “He’s been a part of them as freshmen and sophomores.”

Speaking of connections, the Maccinis are related to the Bagonzis. Rob Maccini is a second cousin of the great coach, while his son, Mike, and nephew, Derek (assistant coach), are third cousins. Rob’s grandfather and coach Bagonzi’s mother were brother and sister.

“Early this year I was coaching a JV game in Gorham and some old timer came up to me and said, ‘You must be a Bagonzi?’’ wrote Rob Maccini via email. “I bet I have had that happen at least five times over my coaching career. I always get a kick out of it.”

THE LEGEND OF BAGONZI AND THE RISE OF WALKER

Any discussion of Woodsville sports is incomplete if the late Dr. John Bagonzi is not mentioned at some point and, to be honest, at length.

Bagonzi’s stature in Woodsville and, indeed, New Hampshire, is legendary. A native of the town, he starred on Woodsville HS teams in the late 1940s in multiple sports, teaming with lifelong friend Bob Smith to give the Engineers an imposing 1-2 pitching punch in baseball.

Both later signed professional contracts with the Boston Red Sox – Smith in 1948 and Bagonzi in 1953. Smith lasted 17 years in the pro ranks (1948 to 1964), including five seasons in the bigs with the Red Sox, Cardinals, Pirates and Tigers.

Bagonzi first went to the University of New Hampshire upon graduation from Woodsville where he starred in both baseball and basketball. While at UNH, he was considered to be the top collegiate pitching prospect in New England. Although signed by the Sox in ‘53 and assigned to the organization’s AAA affiliate in San Francisco, military service interrupted his baseball career. Bagonzi served two years in the U.S. Army as a commissioned officer.

He returned to baseball in 1956, briefly pitching for the Red Sox organization before arm trouble ended that dream after eight games.

With a Master’s degree from Indiana University and pursuing his Ph.D, Bagonzi returned to Woodsville where he went on to exert his remarkable influence as a high school coach and educator for more than a quarter of a century.

Bagonzi coached multiple sports, but his most significant impact came in baseball and basketball where he guided Woodsville teams to 12 state titles – seven in baseball and five in basketball.

Of particular note, 10 of those championships came during the span from 1968 to 1977 in Class M (Division III). On four occasions, Woodsville won the “Daily Double” – basketball and baseball championships in the same school year.

Two of his baseball pitchers – Steve Blood (1971) and Jim MacDonald (1977) – were drafted by major league teams. Blood pitched five years in the Minnesota Twins organization, while MacDonald threw for seven seasons with various Houston Astros farm clubs. Bagonzi also instructed Chad Paronto, a 1993 Woodsville HS grad and son of a former player, Dana Paronto, who at one time held the NHIAA Class M hoop tournament record for most points in a championship game (34, 1971). Chad pitched seven years in the majors with four teams, enjoying his best seasons with the Atlanta Braves in 2006 and 2007.

In 1964, when Woodsville won the Class M baseball title over Charlestown, 3-2, the winning run was scored on a squeeze bunt in extra innings. Hits were hard to come by in that game for the Engineers, who managed just two off Charlestown’s imposing junior ace, a strapping lad whose name still resonates across the state – Carlton Fisk.

Bagonzi won 361 games as a basketball coach and recorded 261 wins in baseball. He has been inducted into multiple halls of fame. In 1991, the year he retired from teaching, the community building in Woodsville was renamed in his honor – the John A. Bagonzi Community Building.

In 2001, Bagonzi wrote “The Act of Pitching” – a definitive study on what it takes to become an accomplished pitcher. Hall of Famer Bob Feller called it “The best book on pitching that I have ever read.” It was reprinted with updates in 2006.

Although coach Walker never played for Bagonzi, he knew of him and can recall as a kid growing up in Woodsville going to games coached by Bagonzi. In fact, the Bagonzis were neighbors of the Walkers, and later in life Bagonzi and his wife, Dreamer, wintered in central Florida. For a number of years, they would spend a week with Walker’s parents enjoying Red Sox spring training games in Fort Myers, Fla.

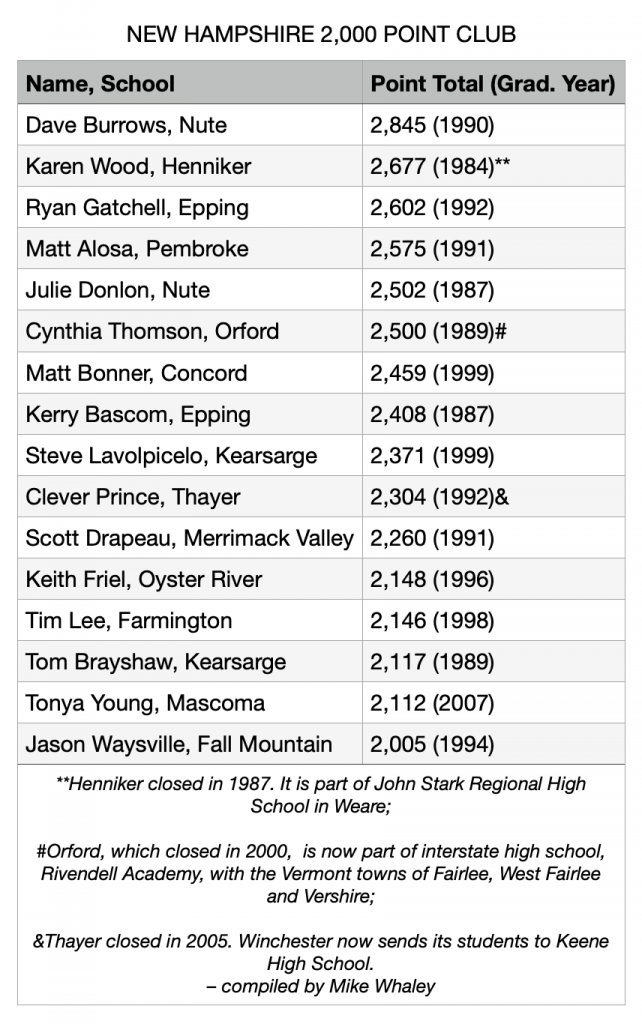

Walker himself played for the Engineers in the 1980s, graduating in 1988 as the school’s second player to reach 1,000 points.

He attended Boston University, graduating with a degree in Human Movement (essentially physical education). He eventually came back to Woodsville and then athletic director Mike Ackerman asked him if he had any interest in coaching JV boys basketball. Walker said yes.

It was 1998. The following year the varsity coach left for a position a little farther north at Profile HS in Bethlehem. Walker was hired as the varsity coach.

He had no long-term goals or aspirations. “I kind of took it year by year,” he recalled.

In the first five years he remembers three of those years being pretty bad – one win, two wins, no wins.

“It was us and Belmont,” Walker said. “If we sweep the series we get two wins and they get zero. If we split we get one win. If they sweep the series we get zero. Those were our big games of the year. That was going to determine if we were going to win any games at all.”

At the time, Woodsville was still in Class M (D-III). Right around the end of those rough years the school moved down to Division IV and success followed. Although he was discouraged, Walker knew there were some good kids coming up. They won five games, then seven and eventually got to .500. They made the final in 2007, a 50-31 loss to Lisbon.

“As you know with any program, once you start winning, those kids who never played a game because (the team) was so bad, now want to play,” Walker said. “You start to go to Plymouth and they watch their buddies in a college gym. All of a sudden they want to play.”

Woodsville has been a constant in the tournament for the last 16 or 17 years, finally breaking through last year to win the title. This winter is Walker’s 24th with the Engineer program as a coach, 23 as their head coach.

Walker recalls interacting with Dr. Bagonzi. They both had the basketball connection at Woodsville as players and coaches, but their primary conversations centered around baseball.

Bagonzi, a respected pitching clinician, was the first person to coach Walker’s son Brendan, an aspiring pitcher, when he was younger. “He was the first one to work with him,” Walker recalled. “The second one who worked with him was a disciple of Mr. Bagonzi – Chris Lavoie.”

Both had a lot to do with why Brendan will hopefully pitch for Stetson.

When Bagonzi was alive – he died in 2014 at 83 – he would drop by the Walker auto dealership in town. “He’d ask how the team was doing,” Walker said. Bagonzi would say, “I’m watching you” or something like that. Walker said they didn’t talk a ton of basketball.

But basketball was undeniably part of Bagonzi’s impressive resume. The five championships came in 1969, 1971, 1973, 1976 and 1977. There were also runner-up finishes in 1960, 1968 and 1975. Along with Bagonzi, names like Burrill, Blood, MacDonald, Pierson and Paronto are forever etched into Woodsville’s rich athletic lore.

The hallmark of those Bagonzi era teams was a fast-paced style. It featured withering full court pressure, which more often than not overwhelmed and demoralized the opposition. If you couldn’t figure out how to handle Woodsville’s vaunted pressure, it was pretty much guaranteed that a long and painful night was in store.

Knowing that history, it certainly made last season’s run to the title all the more compelling and satisfying.

“Growing up you heard a lot about those ‘70s’ teams coached by Mr. Bagonzi,” said Mike Maccini, a third cousin of the great coach. “They’re pretty legendary. There was definitely that 44-year (drought) hanging over us going into the tournament, especially when we got down to the final four and the championship.”

POISED TO DEFEND

Going into the 2021-22 season, Woodsville found itself cast as a favorite, something it hadn’t experienced since the Bagonzi teams of the 1970s.

“Last year there wasn’t much pressure on us,” Flocke said. “We weren’t expected to do much. This year it’s definitely different. We just have to play like we don’t have a bull’s eye on our back; play like the bull’s eye on every team we play against.”

So far, mission accomplished. The Engineers have maintained their resolve.

“Last season’s over,” Walker said. “Nobody cares about last season. Yeah, we’ve done well so far. The important season is coming up. We’ve got to stay focused for that. That’s what I think they do at practice. They have a long-term goal that keeps them going.”

It was good for Woodsville, in retrospect, that the one Lin-Wood game and the two Littleton games got postponed to the end. Instead of finishing their season on Feb. 15 and waiting almost two weeks for their first playoff game, the Engineers were able to stay active.

“It will give us a good idea of what we need to work on going into the playoffs,” Walker said.

The coach has worked hard to keep the team focused and not let them get too full of themselves. It’s been hard because the North Country usually has three or four top-tier teams. This year it’s Woodsville and, really, everybody else. The Engineers beat Littleton, the second best team in the north, by 24 and 21 points, respectively, in the past week.

Walker noted that the second Littleton game on Wednesday, although they won by 21, it was a five-point game in the third quarter. “It was good to have that game leading up to the playoffs,” he said. “Because you’re going to see those types of games in the playoffs.”

With its four starters back, and then a rotating trio of youngsters completing the set as the fifth starter, Woodsville is extremely good. Flocke made this concise analysis of why Woodsville is tough to play against. “We never let up,” he said. “We work hard every minute that we’re out there. One of the biggest things is that we put constant pressure on the ball. We’re always trapping, playing man to man defense as much as we can.”

Tenney-Burt is a bonafide scorer. In late January, he scored his 1,000th career point during a game at Colebrook. His numbers include his freshman year at Lisbon.

“He can shoot,” Walker said. “He can take it to the basket. He’s not just a jump shooter. He may have started that way his sophomore year, but now the last couple of years he’s been more active about taking the ball to the basket, scoring in different ways, instead of just relying on the outside shot.”

Davidson is the Engineers’ inside presence. “I think that’s something we were missing until last year,” Walker said. “I think we really started getting him in the post and getting easy baskets. We were a team that kind of relied on the outside game quite a bit. Last year he was able to get us layups and get to the foul line, get us easy buckets.”

Flocke is the team’s top defender. He always guards the best player on the other team. Walker said he has also developed his shot over the last couple of years. “He’s invaluable,” the coach said. “He is so good at both ends of the floor. He’s a worker.”

In December, Flocke missed four or five practices. “I told my assistants, ‘these practices are half what they are when you have Elijah here with his energy.’”

Maccini has done a nice job slipping into his new role as a dependable point guard. “He’s not going to hurt you,” Walker said. “He may not be the flashiest guy out there, but he makes the right decisions. He can hit open shots and play good defense. He’s a solid point guard. The key to everything is not turning it over. He doesn’t turn it over.”

Having those four back, a year older, stronger and better, has certainly elevated Woodsville’s status, not only in the north, but in the state.

“When you lose one player and you won it last year, you’ve got to win it again?” Walker said. “We told the kids obviously when you win it there’s a target on your back. There’s some good teams in the south that some people think are as good if not better than us. A lot of people think Concord Christian is better than us.”

Let them think that, Walker feels. “I’ll take my five and my team against those guys down there and see how we do.”

The other three who share minutes at the fifth spot as well as providing valuable minutes off the bench to spell the other four starters are freshmen Landon Kingsbury and Connor Newcomb, and sophomore Jack Boudreault. “They’re three kind of different players,” Walker said. “It all depends on what the other team is doing. … We use what the other team is doing to determine how we rotate those three. We mix and match with what we need at the time.”

The south does have some top-notch teams. Along with No. 2 Concord Christian (17-1), No. 3 Epping (14-4), No. 5 Portsmouth Christian (14-4), No. 6 Holy Family (14-4) and No. 7 Derryfield (12-6) have all been very solid.

“Is the talent in the south?” Walker asked. “It may well be. We’ll find out when the playoffs start.”

Truth.

RIM NOTES. Going into this week, Tenney-Burt was leading the Engineers in scoring (18.8 ppg). He is followed by Flocke (11.7), Davidson (8.7), Kingsbury (7.8) and Maccini (6.0). … Dr. Bagonzi coached Woodsville to 13 state titles in all. His last came in 1988 in girls cross country. … Since then and before last year, the Engineers have had some success in other sports. The girls soccer squads won back-to-back crowns in Class M-S in 1993 and 1994. Boys soccer hit pay dirt in Class S in 2004 and 2005, and softball is the most recent to capture titles in Class S (2010, 2013) as well as last spring. … Carlton Fisk is mentioned above for baseball, but he loved basketball and was quite good at it. In fact, he still holds a Class M (Division III) tournament record for field goals in a single game with 19 (drained in 1965 semis) that he shares with Woodsville’s Stephen Elliott, who hit the same number in 1964. Elliott also shares the tourney mark for most points in a game (45) with Farmington’s Tim Lee.

For feedback or story ideas, email jamsession@ball603.com.

Jeff accepted a scholarship to Boston University, but never played under Pitino. On the eve of the season, the coach took a position as an assistant with the New York Knicks – a season that Jeff ended up spending on the BU bench.

Jeff accepted a scholarship to Boston University, but never played under Pitino. On the eve of the season, the coach took a position as an assistant with the New York Knicks – a season that Jeff ended up spending on the BU bench. It was a great experience. It’s where he met his wife, Janel.

It was a great experience. It’s where he met his wife, Janel. From Ball he learned how to run a program, including how to increase your participation numbers. “I developed that over the years,” Holmes said. “We’ve got good numbers for freshman and JV. We have a lot of competition for spots.”

From Ball he learned how to run a program, including how to increase your participation numbers. “I developed that over the years,” Holmes said. “We’ve got good numbers for freshman and JV. We have a lot of competition for spots.” Although there was success the two years after that, there was also frustration because of the pandemic.

Although there was success the two years after that, there was also frustration because of the pandemic.

Gilford plays a fast-paced game, pressing on defense and pushing the ball on offense. As a point guard, Jalen pilots the offense. “He can lead us in rebounding,” the coach said. “He leads us in assists. He can lead us in scoring on any given night.

Gilford plays a fast-paced game, pressing on defense and pushing the ball on offense. As a point guard, Jalen pilots the offense. “He can lead us in rebounding,” the coach said. “He leads us in assists. He can lead us in scoring on any given night. Acquilano replaced long-time coach Chip Veazey, who coached Gilford for 35 years and over 400 wins, including its first state title in 2004.

Acquilano replaced long-time coach Chip Veazey, who coached Gilford for 35 years and over 400 wins, including its first state title in 2004. Although all three played multiple sports growing up, last season was the first time that all three played together on the same team. “We actually didn’t think we were going to get along,” Jalen said. “We don’t usually (get along) at the house. But it was fun.”

Although all three played multiple sports growing up, last season was the first time that all three played together on the same team. “We actually didn’t think we were going to get along,” Jalen said. “We don’t usually (get along) at the house. But it was fun.” All teams at some point in a season face adversity. Gilford’s came in unlikely fashion. During a game with White Mountains on Jan. 21 (a 46-35 win), Jalen was surprisingly assessed with two technical fouls – one for hanging on the rim after a partially-missed dunk that he actually tipped in and the second for saying something under his breath to a teammate regarding the first technical. Coach Acquilano felt both Ts were questionable.

All teams at some point in a season face adversity. Gilford’s came in unlikely fashion. During a game with White Mountains on Jan. 21 (a 46-35 win), Jalen was surprisingly assessed with two technical fouls – one for hanging on the rim after a partially-missed dunk that he actually tipped in and the second for saying something under his breath to a teammate regarding the first technical. Coach Acquilano felt both Ts were questionable. “We’ve got to focus,” Isaiah said. “I think we can’t play down to the competition. We have to rise above anybody that we play.”

“We’ve got to focus,” Isaiah said. “I think we can’t play down to the competition. We have to rise above anybody that we play.” Gilford plays its final game Friday at Berlin. The 15-team tournament starts Tuesday with opening-round games. The Golden Eagles will likely earn a first-round bye, which means their first game will be in the quarterfinals Friday, Feb. 18, at home. The semis are set for Feb. 22 at Bedford High School with the championship scheduled for Feb. 26 at Keene State College.

Gilford plays its final game Friday at Berlin. The 15-team tournament starts Tuesday with opening-round games. The Golden Eagles will likely earn a first-round bye, which means their first game will be in the quarterfinals Friday, Feb. 18, at home. The semis are set for Feb. 22 at Bedford High School with the championship scheduled for Feb. 26 at Keene State College.

“It was all about scoring,” recalled Tyrone. “So me and Ant were always trying to do it ourselves. Midway through the season we realized that (Chase) kept repeating himself, that it’s more than just scoring. You have to get your teammates involved and share the ball. That gives your teammates more confidence.”

“It was all about scoring,” recalled Tyrone. “So me and Ant were always trying to do it ourselves. Midway through the season we realized that (Chase) kept repeating himself, that it’s more than just scoring. You have to get your teammates involved and share the ball. That gives your teammates more confidence.” Both hit the weight room and put on at least 15 pounds each.

Both hit the weight room and put on at least 15 pounds each. The Astros bounced back from the BG loss to beat rival Londonderry, 64-58, and Bedford, 69-50. The Chinns combined for 23 and 24 points in those two wins. The Bedford win was particularly telling.

The Astros bounced back from the BG loss to beat rival Londonderry, 64-58, and Bedford, 69-50. The Chinns combined for 23 and 24 points in those two wins. The Bedford win was particularly telling. Anthony agrees. “Our defense is really why we’re good,” he said. “All five guys can defend. We’re really good at playing team defense.”

Anthony agrees. “Our defense is really why we’re good,” he said. “All five guys can defend. We’re really good at playing team defense.”

Hefferon, a six-foot junior point guard, is the key. Early in this season, he has already displayed his vast potential as one of D-III’s top scorers (20.5 ppg), although the ‘Toppers are off to a lukewarm start with a 2-2 mark.

Hefferon, a six-foot junior point guard, is the key. Early in this season, he has already displayed his vast potential as one of D-III’s top scorers (20.5 ppg), although the ‘Toppers are off to a lukewarm start with a 2-2 mark. Covid was the X factor. Players were constantly getting sick. He recalls going to some practices with only five or six players in the gym. “We couldn’t run full drills sometimes,” Hefferon said.

Covid was the X factor. Players were constantly getting sick. He recalls going to some practices with only five or six players in the gym. “We couldn’t run full drills sometimes,” Hefferon said.  Hefferon may need to get to a higher level as the Hilltoppers have a brutal stretch looming ahead in January with difficult games with Campbell, Gilford, St. Thomas and Mascenic.

Hefferon may need to get to a higher level as the Hilltoppers have a brutal stretch looming ahead in January with difficult games with Campbell, Gilford, St. Thomas and Mascenic.

Games were the worst.

Games were the worst.